FACE UP OR FACE DOWN?

The stress-reduction potential of massage therapy is one of the greatest tools of preventive medicine. Despite its obvious simplicity, the execution of a stress-reduction massage can be greatly enhanced by the application of important tips which frequently remain unknown by already practicing therapists or instructors in massage schools. The topic of this article is simple: How best to begin a stress-reduction session — with the client positioned on their back or on their stomach?

In science there are no small or unimportant topics, and every detail counts when wanting to do things right. This is also true of the science of stress-reduction massage. It is obvious that the major goal of stress-reduction massage, as the name suggests, is stress reduction, and the practitioner must use all the tools at his or her disposal to achieve this goal to the greatest degree possible.

Let us compare, for a moment, the sought-after effects of a stress-reduction massage session to the action of quicksand. As soon as the client gets onto the table, every move, technique or detail is aimed at influencing the state of the client’s body and slowly submerging them into the deepest state of relaxation. If, after a stress-reduction session, the client feels pumped up to go to the gym and exercise, the practitioner used stimulating therapeutic massage or sports massage protocols, but it was not a stress reduction session. From this perspective of sedative versus stimulating effect, the order chosen regarding the client’s positioning on the table becomes very important. Our experience with students during educational seminars has allowed us to observe that many instructors teach students to begin stress-reduction massage sessions with the client positioned on the stomach. To our reasonable questions as to why, we’ve usually received the following answer: “I was taught in school that the majority of the tension the client carries is in the shoulders and the lower back; and that therefore, to reduce tension and stress as soon into the massage as possible, the therapist should address these areas first.” Yet, an explanation such as this does not reflect the basic scientific principles of stress-reduction massage.

The majority of the functions of our body, including stress- and relaxation responses, are under the involuntary control of the autonomic nervous system, which has two divisions: the sympathetic and the parasympathetic. The sympathetic division is responsible for producing the body’s reactions to physical or emotional stress, while the parasympathetic division is responsible for producing the opposite response — that of relaxation.

The client who rushes to the appointment to arrive on time is under the influence of increased sympathetic tone, and it is then the massage practitioner’s job, in 30 to 120 minutes, to turn the tables around so as to decrease the activity of the sympathetic nervous system and increase parasympathetic tone.

Another important point to consider is the distribution of the large muscle groups on the anterior and posterior surfaces of the body. It is obvious that the larger muscle groups are located mostly on the posterior body surface (back, gluteal area, legs, etc). The large muscle groups are the biggest blood depot given that they consume the largest portion of oxygenated blood. Also, larger muscles have more peripheral receptors located in their tissue.

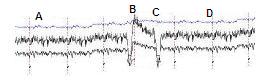

The final element relevant to our discussion is the correlation between stress and open or closed eyes. Let’s look at Fig. 1, which shows a normal electroencephalogram (EEG) of the brain. The part A of the EEG was recorded while the subject had kept his eyes closed for 10 minutes. At point B, the subject opened the eyes, and, as can be seen, the EEG changed dramatically exhibiting sensory stimulation to the brain. At the point C the subject closes eyes and the last part of the EEG (part D) exhibits the EEG of the same subject after the eyes closed again.

Let’s take as an example the average client who is healthy, doesn’t suffer from any pain or uncomfortable sensations, and is scheduled for an hour-long session of stress-reduction massage. The ultimate goal of the treatment is to inhibit sympathetic tone, increase parasympathetic tone, and restore the normal, balanced interplay between both divisions of the autonomic nervous system.

As a result of everyday life, problems in the workplace, perhaps tension at home, and even running late for the appointment, the client’s sympathetic nervous system is flying high. He or she finally gets onto the massage table. Now, we will follow the physiological chain of events depending upon whether the session is begun with the client positioned on their stomach or on their back. Also let’s assume that the client closes eyes after first 10-15 minutes closed during the entire session. We will use Fig. 2 as a guide.

Thin Solid line – stimulation of the brain by visual system

Dashed line – middle point of the massage session

The practitioner starts to work on the large muscle groups of the back and lower extremities. As a result, venous and lymphatic drainage from these tissue increases, overall tension decreases, and there is significant inhibition of sympathetic tone (see Fig. 2, #1). In this position, the client will be more likely to close their eyes during this part of the treatment because their face is in the cradle.

After thirty minutes (point B), the client will turn over onto the back. While doing so, he or she will open eyes, which will automatically increase sympathetic tone (see Fig. 2, #2). For the rest of the session, the practitioner will work on the anterior surface of the client’s body, which has a lesser amount of soft tissue. In so doing, a lesser number of peripheral receptors will be desensitized, and as a result, sympathetic tone will be inhibited to a lesser degree (see Fig. 2; #3).

The practitioner starts to work on the scalp and face. This is a highly effective approach for bringing about the initial inhibition of the sympathetic nervous system. Because there are less peripheral receptors on the anterior surface of the body, the initial inhibitory effect on the sympathetic nervous system is less pronounced (see Fig. 2, #4).

Some clients, during the first part of the session, keep their eyes open and/or engage in conversation with the practitioner. While it is of value for the practitioner to maintain such conversation in order to establish a rapport with the client, it is wise to gradually reduce conversation so as to allow the client’s mind to become submerged in a state of deeper and deeper relaxation.

The starting position on the back fosters a very gradual inhibition of the sympathetic nervous system during the first part of the session and it paves the road to the deeper state of relaxation when the client later turns onto his or her stomach (see Fig. 2, #5). While turning the client onto the stomach will also require them to open his or her eyes (if they where closed), the stimulating impact of this “turning point” on the sympathetic nervous system will be less pronounced, given that the overall inhibition of sympathetic tone is less while the practitioner works on the anterior surface of the body, as compared with the posterior surface.

Parts #2 and #5 on the Fig. 2 illustrate this statement. Point A indicates the level of brain stimulation by the visual system at the moment the client opens the eyes while turning over. (The level of brain stimulation is the same, with eyes open in the resting state, regardless of what depth of relaxation preceded it.) Now, let’s compare both diagrams: if the practitioner begins the session with the client on the stomach and works on the posterior surface of the body, he or she leads the client into the deepest state of massage-induced relaxation; and at the moment the client opens the eyes, as they turn over (point B), the client’s sympathetic nervous system is roused from a deeper state of relaxation (see Fig. 2, #2) than had the practitioner begun the session with the client positioned on the back. In the latter case, the activation of the sympathetic nervous system upon the client’s turning over and opening the eyes is more moderate (see Fig. 2, #5), as the client will not have yet reached the deepest level of relaxation. Work, during the second half of the session, on the posterior surface of the body (with its larger mass of soft tissue) will find the client at the deepest state of relaxation by the end of the session (point C).

Let’s now look at venous and lymphatic drainage in both positions, on the back and on the stomach. As the practitioner works on the anterior surface of the body, the lymphatic system receives the drained lymph and interstitial fluid from the soft tissue of the anterior surface — which is less voluminous than the same from the more abundant soft tissue of the posterior surface. The system is able to deal with this lesser voluminous fluid prior to having to receive the greater volume that will arrive once the practitioner begins to work on the posterior surface of the body.

In the opposite scenario (that is, with the client initially positioned onto the stomach), the system’s ability to deal with the fluid in a timely manner is challenged, as it receives the greater volume of fluid from the posterior surface’s soft tissue first. Moreover, after the clients turn onto their stomach after the first half of the session, the force of gravity, in combination with the massage strokes directed along the major routes of lymphatic drainage, will drain the large muscle groups on the posterior surface of the body, and this will be the final effect of the session.

When the client then gets up and starts to walk, bend, etc., the muscle pump (as it is called) will immediately kick in and will work to maintain the level of drainage achieved during the session. In this way, the overall stress-reduction effect of the massage will be much more lasting — an effect that cannot be achieved if the client has been positioned on their back for the final half of the session.

We hope we have persuaded our readers as to the necessity of beginning the massage session with the client positioned on their back; and for those readers who already correctly position their clients in this way, we are happy to have, with this article, justified their approach.

John Antonopoulos, LMT, has been practice massage therapy for 25 years. He has studied with the distinguished Paul Andres of Alsace, as well as at Montreal’s Kine-Concept Institute. He conducts a private practice in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. He can be reached by e-mail: ianosmammio@gmail.com

Category: Stress Reduction Massage