We consider both parts of this article precious professional pieces. First of all, the article illustrates the author’s profound understanding of the science behind massage therapy, great clinical skills, while it also shows her deep compassion and dedication to patients who desperately need help.

This last aspect brings us to the second important feature of the article. While reading articles and various publications on Oncology Massage, it is obvious to us that they present important, but only a partial picture of a much more complex clinical issue. Yes, full body massage sessions are an important tool to reduce stress which accompanies each cancer patient and ravages their souls from the inside. However, it is only one side of Oncology Massage and another even more important aspect of Oncology Massage completely absent from all articles and publication we’ve read so far in American Oncology Massage literature. Vanessa Sifontes fills this unfortunate gap and her articles demonstrate how far therapists may and must go to help cancer patients.

So, if you are practicing Oncology Massage please consider branching yourself further, into Oncology Massage Rehabilitation (OMR), because there is a very limited number of therapists who do it correctly and cancer patients are in great need of your services. While reading this article you may witness first hand how much therapists can help patients who are going through cancer therapy. Oncologists compete for Vanessa’s treatments because they see how much her therapy helps cancer patients. Please consider adding OMR to your basic Oncology Massage!

Dr. Ross Turchaninov, Editor in Chief.

ONCOLOGY MASSAGE REHABILITATION.

PART II: TREATMENT STRATEGY

by Vanessa Sifontes, PORi Certified Oncology Rehabilitation Specialist

In Part I of this article (please click here: https://www.scienceofmassage.com/2019/03/oncology-massage-rehabilitation-part-i-newest-scientific-data-commonly-used-cancer-treatments-and-their-side-effects/), we discussed general principles of Oncology Massage Rehabilitation (OMR) on patients as well as the most common side effects of modern oncology treatment.

In Part II I would like to discuss treatment strategy and how manual therapy and massage may diminish the side effects of cancer therapy and help soft tissue rehabilitation. To better illustrate the concept of rehabilitation I will use cases of successful somatic rehabilitation from our clinic.

FASCIA REHABILITATION

It would be impossible to discuss manual rehabilitation of cancer patients without a clear understanding of fascia’s role. Fascia as defined by Schleip et al. (2012) is a “fibrous network, a single continuity within the body from the undersurface of the skin, all the way down to the nucleus of the cell.”

It is imperative to remember that fascia is also a sensory organ, composed of six times as many sensory nerves as the retina, which is thought to be the richest sensory organ in our body (Grunwald, 2017). Addressing cancer patients with OMR leads to restoration of fascia structure and function greatly affected by cancer and oncotherapy.

During OMR sessions the therapist stimulates mechanoreceptors located in the fascia, restores normal bioelectricity with soft tissues, reduces tension in the extracellular matrix (ECM), regulates production of cytokines (the substances are playing a major role in local inflammation of tissues and organs), increases ATP (energy source for muscle contraction and relaxation) production by the mitochondria, and contributes to entire fascia reconstruction by stimulating normal collagen production. Clinically OMR improves neuromuscular efficiency, decreases muscular hypertonicity, improves ROM, restores soft tissue drainage and decreases pain and discomfort.

Cancer starts at the cellular level and in order to successfully rehabilitate cancer patients and address side effects of its treatment, we have to work at the same level. This is why addressing the fascia and muscles with myofascial work, as a component of OMR, is a critically important first line of defense against soft tissue fibrosis due to radiation, chemotherapy or inactivity which many cancer patients suffer during long periods of oncotherapy.

As we discussed in Part 1, rigidity of the ECMs is one of the key factors which affects cancer microenvironment in the affected tissues and contributes to tumor growth, invasion and malignancy (Butcher et al., 2009). There are no other clinical tools to decrease rigidity of the ECM besides manual work which allows restoration of tissue elasticity and maintenance of ECM’s ‘fluidity.’ This is why OMR is such a critical component of cancer therapy.

Another aspect is loss of muscle activity during onco-therapy due to fatigue triggered by chemotherapy and radiation. Unused skeletal muscles quickly become atrophic and it triggers fascia scarification due to excessive connective tissue proliferation, which further limits muscle contractions and diminishes the range of motions. Utilizing all of the tools in therapist’s toolbox greatly facilitates functional gains.

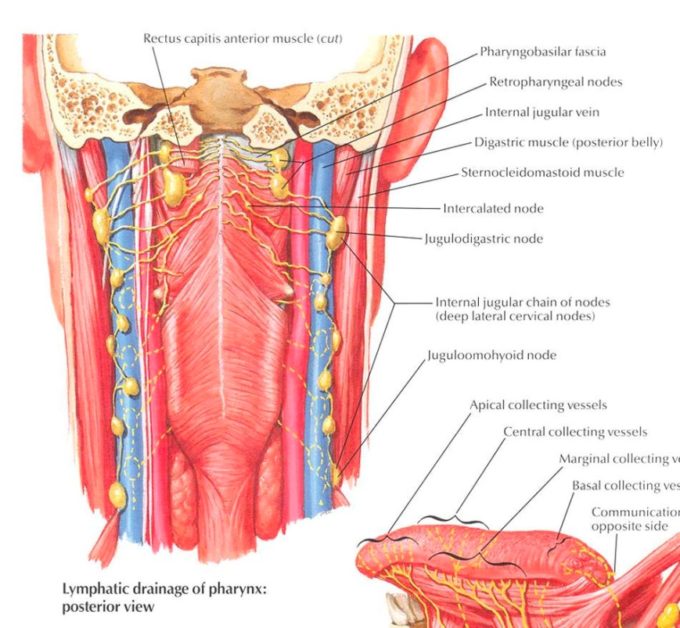

Let me define the common steps of a rehabilitation of fascia for Head&Neck Cancer (H&HC) patients. Let’s look at what muscles and fascia, which covers them, are in the radiation (XRT) field, and how their damage triggers soft tissue constrictions and weakness. Fig. 1 illustrates head and neck radiation field dose map.

Red colored area is the location of primary cancer and its color indicates the largest power of radiation (70Gy) delivered to the tumor. The change in color represents lesser radiation impact (24Gy) on the soft tissues around the tumor. However, repetitive XRT even with lesser power has a profound impact on the function of soft tissues.

Fig. 1. Head and neck radiation field dose map

Looking at the potentially affected muscles (Fig. 1) from a functional perspective it is obvious that they are responsible for rotation, lateral flexion, flexion and extension of the cervical spine. XRT greatly affects cervical muscles on all levels, making them short and tense due to dramatic increase of pressure in the extracellular matrix. This pressure, besides limiting tissues’ elasticity and their function is one of the major contributing factors in cancer metastasizing (as we discussed in Part I). Thus, decompressing soft tissues and extracellular matrix besides restoring tissue function will contribute to the stability of oncotherapy’s clinical results.

However, there is another aspect of soft tissues in the neck – they are key participants in the act of swallowing. The swallowing mechanism is one of the most intricate mechanisms in our body’s somatic functions. It relies on precise interactions between many somatic structures and even the slightest delay or failure of even one of them greatly affects food and liquid consumption. I compare the simple act of swallowing with a perfectly performing orchestra which flawlessly performs a symphony.

When neck muscles become tight and fibrotic, due to XRT, the range of motion of the patient’s larynx dramatically decreases and the consequences could be catastrophic. The most common side effect is food and liquid aspiration into the patient’s airway and lungs which is the major cause of pneumonia. Mix pneumonia with immunosuppression which all patients with cancer go through and it becomes deadly complication.

LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

Another aspect of the OMR is its impact on the lymphatic system. Travel and Simons identified tension in scalenes, subscapularis, theres major and pectorals minor as one of possible causes which affects lymphatic drainage from the upper body. In 1994 Kuchera and Kuchera reinforced the fact that scalenes “have shown reflexly to suppress lymphatic duct peristaltic contractions.”

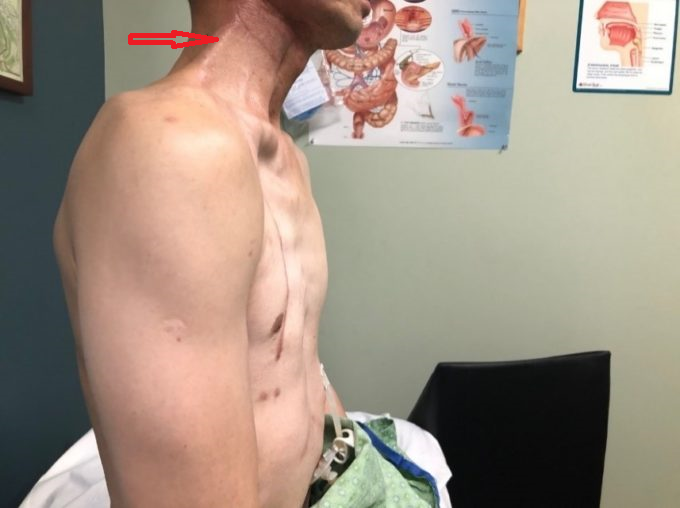

Here is another example of how important OMR is for the rehabilitation of patients with H&NC. Behind the mandibular ramus on the posterior surface of pterigoideus external muscle in the pharyngeobasilar fascia (Fig.2 blue line) lies a pack of retropharyngeal lymph nodes (see Fig. 2, green line) which later connected to the chain of deep lateral cervical lymph nodes (see Fig. 2, , green line) which later connected to the chain of deep lateral cervical lymph nodes (see Fig. 2, red line)

Fig. 2. Anatomy of inner neck with deep lymphatic system

This pack of lymph nodes is a very important component of a deep system of cervical lymphatic drainage and even in a normal anatomical scenario operates in a very tight spot being squeezed between the upper part of the pharynx and the arch of the atlas while the belly of rectus capitis muscle is positioned on top of it.

Therefore, releasing tension in these muscles and decompression of first cervical vertebra will greatly assist in the deep lymphatic drainage which if it fails is responsible for internal or deep lymphedema. Fighting and preventing deep lymphedema is critically important for rehabilitation of H&NC patients since there is very limited space in the neck and any additional pressure even in the form of extra fluid triggers a variety of secondary complications.

Thus, therapists can restore and assist in deep lymphatic drainage by targeting soft tissues in the area behind the mandibula and first cervical vertebra and it becomes vital support for the H&NC patients to deal with side effects of oncotherapy. Let me illustrate the clinical significance of OMR for the H&NC patients based on experiences from our clinic.

CLINICAL CASE #1

In 2018, we treated a patient who had completed treatment for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the base of the tongue back in 2005. At the initial evaluation the patient presented with reduced cervical ROM and painful and consistent spasms of cervical muscles throughout the entire day. The intensity of spasms and pain increased greatly at the end of each neck movement and every time he was getting in and out of bed. Patient’s initial cervical ROM was:

Cervical Rotation to the right – 39 degrees

Cervical Rotation to the left – 35 degrees

Lateral Flexion to the right – 14 degrees

Lateral Flexion to the left – 14 degrees

Flexion – 44 degrees

Extension – 13 degrees

Our therapy is focused on addressing the drainage, fascia and tension in the levator scapula, upper trapezius, scalenes, SCM, and pectorals minor muscles. At the end of fifth session his ROM measurements were:

Cervical Rotation to the right – 68 degrees

Cervical Rotation to the left – 70 degrees

Lateral Flexion right – 20 degrees

Lateral Flexion left – 20 degrees

Flexion – 55 degrees

Extension – 32 degrees

The patient’s neck never went into spasm after the first session and to this day, spasms have not returned. The patient does his daily stretching sessions religiously and despite living in NM he flies to CO twice a year to let us work on him as a supportive measure.

CLINICAL CASE #2

A 51-year-old female with a long (30 years) history of tobacco use was diagnosed with Squamous Cell Carcinoma of buccal mucosal which had spread to the submandibular salivary gland. The tumor was encapsulated with no further extension or lymph node involvement.

Modified radical neck dissection on the right side, and partial anterior glossectomy with anterolateral flap was performed by a surgeon. Fig. 3 illustrates her neck at her first visit to our clinic. Severe edema above the scar all way to the right side of her face is clearly visible. Pay attention to the red discolorations on the check and chin above the scar due to the severe venous stasis.

Fig. 3. Patient’s neck at first visit to our clinic.

We started therapy twice a week in order to improve neck drainage and scar elasticity. Fig. 4 illustrates the patient’s neck after 10 sessions of OMR. Changes in scar density with restoration of color on the face are notable, but the patient still exhibited submandibular edema above the scar.

Fig. 4. Patient’s neck after 10 sessions of OMR

Approximately at the same time the patient began XRT while we continued to work on her neck. Fig. 5 illustrates the patient’s neck after first radiation. Brown skin pigmentation on the cheek is skin reaction to XRT.

Fig. 5. Patient’s neck after first radiation therapy

Fig. 6 illustrates the clinical picture after two weeks of radiation therapy. Her skin now exhibits severe radiation dermatitis with skin damage and scaling.

Fig. 6. Patient’s neck after two weeks of radiation therapy with radiation dermatitis

Fig. 7 illustrates the neck of our patient after three weeks of XRT. At that time thanks to correct OMR symptoms of her radiation dermatitis improved, but newly appeared tissue fibrosis with muscle shortening is clearly visible (indicated by yellow circle). These changes required our immediate attention in order to prevent permanent scarification and minimization of functional loss in ROM.

Fig. 7. Patient’s neck after three weeks of XRT

Yellow circle – newly developed soft tissue fibrosis

Fig. 8 illustrates our patient’s neck at the first and last session of somatic rehabilitation.

Fig. 8. Patient’s neck on the first and last session of OMR.

The reddish color of the skin on the face and neck after session #17 is the result of cumulative burn by XRT which disappears with time. Redirection of the lymph drainage almost completely eliminated edema and it greatly helped with formation of scar with low rigidity and lesser stiffness in the surrounding tissues. No tissue fibrosis visible (please compare with Fig. 7)

We were able to decrease symptoms of radiation dermatitis while successfully fought with soft tissue fibrosis. Today her scar is barely noticeable with full Cervical ROM, normal swallowing and breathing. The patient completely recovered, returned to full work and a productive social life and recently got promoted at her job.

CLINICAL CASE #3:

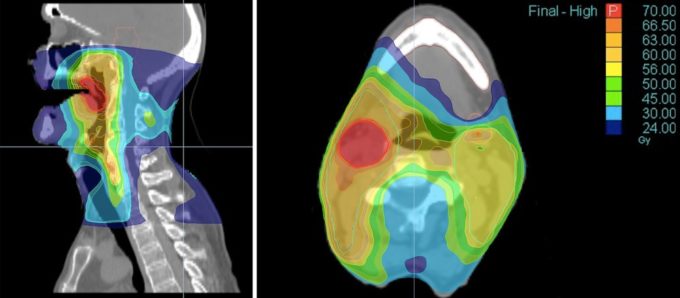

A 46-year-old male was diagnosed with Stage IV of Nasopharyngeal cancer in 2007. Patient treatment started with chemoradiation therapy (XRT with cisplatin and 5 FU) with initially good results.

In 2012 the neck cancer came back and the patient underwent subtotal neck resection with full dosage of neck radiation for the second time. In 2017 the patient’s cancer came back again and this time the surgeon was forced to do a neck resection with pectoralis major flap since there are no soft tissues left on the neck. Surgery was followed with a third time nasopharyngeal radiation. All these XRTs triggered severe soft tissue fibrosis which is visible as a string of tension on patient’s lateral neck all way to the lower jaw. Fig. 9 illustrates initial clinical picture.

Fig. 9. Initial clinical picture

Red arrows – area of soft tissue fibrosis

Here is the patient’s Cervical ROM before and after somatic rehabilitation in our clinic:

Cervical rotation to the right:

Original – 25 degrees

After the therapy – 53 degrees.

Cervical rotation to the left:

Original – 50 degrees

After the therapy – 65 degrees.

Mouth opening:

Original – 15mm

After the therapy – 21mm.

Fig. 10 illustrates the patient at the end of somatic rehabilitation with soft tissue fibrosis on the right dramatically decreased. The string of tissue tension on the right lateral neck is less visible and soft tissues became soft during the palpation.

The time difference between initial evaluation and first improvement was 8 sessions.

Currently, the patient is on immunotherapy (Keytruda) that has been shown to have good results especially with a recurrent cancer. The patient is a FedEx delivery driver and he has come back fully to his job.

These patients are the simplest clinical cases from our clinic, but they greatly illustrate the need for cancer patients in correctly applied protocol of OMR (MLD + Myofascial work) as soon as cancer therapy starts. Loosing precious time may produce grave complications for H&NC patients and it may dramatically affect their somatic functions.

The more experience I gain through research, work on patients, and communications with colleagues, the more frequently I find myself returning to the basic concepts of soft tissue rehabilitation: Cell. Sarcomere. Fascia. Therapist’s Hands.

REFERENCES

Butcher D.T., Alliston T., Weaver V.M. A Tense Situation: Forcing Tumor Progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009; 9(2): 108-122.

Grunwald M. Homo Hapticus. Droemer HC, 2017

Kuchera W.A., Kuchera, M.L. Osteopathic Principles in Practice. Greyden Press LLC, 1994

Schleip R., Thomas W. Findley T.W., Huijing P. Fascia: The Tensional Network of the Human Body: The science and clinical applications in manual and movement therapy. Churchill Livingstone, 2012.

Travell, J.G., Simons, D.G.: Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction. The Trigger Points Manual. “Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1983.

Category: Medical Massage

Tags: 2019 Issue #2