THE SCIENCE OF PALPATION

PART I.

by Ross Turchaninov, MD

This is our third article about evaluation of patients written for Medical Massage practitioners and those who would like to enter this exciting field. Our first article, “The Science of Clinical Interview,” was published in #1 Issue 2012 of JMS and the second article, “The Science of Visual Observation,” was published in #2 Issue, 2015 of JMS.

Palpation is a vital skill for the therapist. Only with fully developed and correctly used palpatory skills is the therapist able to conduct detailed examination of the soft tissues on a layer by layer basis and formulate correct treatment strategy.

No one is born with the exceptional ability to palpate. These skills must be developed and constantly updated by the therapist if he or she would like to be clinically efficient.

To fully understand and implement palpatory skills the therapist must understand how the somatosensory system works. This system is responsible for delivering to our brain enough data to develop sensations we feel: temperature and texture of surrounding objects, vibration, pressure in the tissues, range of motions, etc. Thus knowing how the somatosensory system operates gives the therapist the foundation and tools for further development and refinement of the palpatory skills. This is why we will start with a short review of the somatosensory system, which relies on the function of four types of peripheral receptors – mechanoreceptors, thermoreceptors, nociceptors or pain receptors, and proprioceptors. For the topic of palpation, the mechanoreceptors and thermoreceptors are relevent and we will concentrate on them.

The Somatosensory System And Palpation

The main palpatory tool is our hands – especially our fingertips. The skin on the palmar surface of the hands and fingers, especially the fingertips, is unique in its structure:

1. Skin on the palms doesn’t have hairs and this is why it is called glabrous skin. The hair follicles have their own receptors (see Fig. 1) and they are firing as soon as the tip of the hair is moved, even before the object gets in touch with the skin surface. Thus the presence of hair on the palms and fingertips will greatly reduce the sensory abilities of the skin.

2. Skin on the palms is second in thickness after soles.

3. It has the greatest concentration of sweat glands (2736 per sq inch versus 554 on the thigh). Excessive moisture creates optimal conditions for the activation of the mechanoreceptors and it helps to grasp objects more securely.

4. The concentration of all sensory receptors on the fingertips is greatest in the body (2500 per cm2). For example, there are 100 touch receptors per cm2 on fingertips versus fewer than 10 receptors per cm2 on the dorsal surface of the hand.

5. Skin ridges on the fingertips have the largest concentration of sensory receptors.

There is a very simple but illustrative Two-Point Discrimination Test which demonstrates the richness of innervation of the fingertips compared to any other parts of the body. If you close your eyes and ask your friend to simultaneously press the tips of two toothpicks into the skin of the index finger you will feel two points of pressure, even if the distance between toothpicks is only 1 mm. At the same time, on the posterior leg, you will feel both toothpicks as one even if they are placed within a distance up to 40 mm (8 inches). Fig. 1 illustrates mechanoreceptors in the skin.

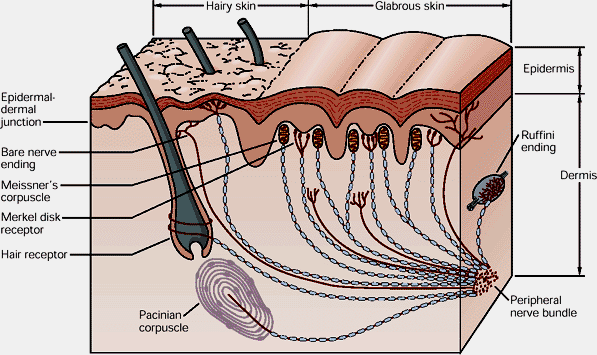

Fig. 1. Mechanoreceptors in the skin

Mechanoreceptors which therapists employ during palpation respond to the different degree of deformation as the initial stimulation. All mechanoreceptors which deliver sensory information to the brain are divided in two groups – rapidly adapting and slowly adapting. This concept is very important for therapists since it directly affects palpation skills. The rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors fire immediately, but with continuous stimulation they very quickly cease the production of nervous impulses (i.e., action potentials) to the brain.

In contrast, slowly adapted mechanoreceptors do not respond to initial stimuli quickly but they continue to fire to the brain, in some cases, even after the initial stimuli are withdrawn.

Merkel’s disks receptors are located in the top layers of the dermis and they detect touch (see Fig.1). They are slowly adapting receptors. Merkel’s disks allow us to detect continued touch and pressure. However, they are very bad at detecting the beginning of touch and pressure.

Meissner’s corpuscle receptors are also located in the top layers of the dermis and detect touch (see Fig.1). They are rapidly adapting receptors. Meissner’s corpuscles are very good at detecting initial touch or pressure but less effective in detecting continuous pressure. The combined information from Merkel’s disks and Meissner’s corpuscles allows us to examine and evaluate texture of an object, e.g. rough patches on the skin in the areas of reflex zones.

Ruffini’s Endings are located in the deep layers of the skin (see Fig.1) and react to stretching of the skin which is an important element of palpatory evaluation and to the pressure stimuli, especially if they are applied under the angle. For example, the therapist will rely on Ruffini’s Endings when he or she uses Dickle’s technique for the examination of Connective Tissue Zones formed in the second level, i.e. superficial fascia. Ruffini’s Endings are slowly adapting receptors.

Pacinian Corpuscles are rapidly adapting receptors and they are primarily responsible for the detection of vibratory stimuli (see Fig.1). For example, the therapist detects the pulsation of the subclavian artery to determine the correct position of the thumb for the examination of tension in the anterior scalene muscle.

The practitioner also uses thermoreceptors during the palpatory evaluation of the soft tissues. Thermoreceptors are found in the dermis layer of the skin (see Fig.1). The following simple experiment illustrates how the temperature receptors work:

Place three tall glasses on the table and pour hot water into the left glass and ice cold water into the right glass. Then pour room temperature water in the middle one. Grab the glass with hot water with one hand while grabbing the glass with cold water with the other. After holding your hands on both glasses for more than a minute, grab the glass with room temperature water with both hands. You will continue to feel that glass is hot by one hand and that it is cold by the other hand despite that water in the middle glass is at room temperature.

Thus the thermoreceptors are the best sensors when they detect fluctuations in the temperature of the object in comparison to the information which was already received and analyzed by the brain. We will come back to this later when we discuss examination of the local temperature of the soft tissues.

Peripheral sensory receptors generate an enormous flow of action potentials through the sensory ascending part of the peripheral nerves all way to the spinal cord where it is initially processed and analyzed and conducted further to the brain where actual perceptions of touch, pressure, vibration, etc. are formed by the cortex based on the obtained data.

The Seven Step Method Of Learning Palpation

In this section we would like to share with readers a very interesting professional suggestion on how to learn and optimize palpation skills. This Seven Step Palpation learning sequence was developed by Aubin et al., (2015) and it is a very helpful guide especially for students and therapists who would like to start or optimize their palpation skills. To make the information from the article easy to follow we present the Seven Step Palpation Method in a more detailed format and from the Medical Massage practitioner’s point of view.

Note that Steps 2-4 are based on visualization principles. Visualization techniques are very helpful when humans learn complex tasks (including palpation) since these techniques help our cerebral reorganization (Jackson 2003). Also you will notice that some steps are labeled “Advanced.” Master the basic steps first, but as soon as you get comfortable with them work on the advanced steps to be able to determine the full clinical picture.

Step 1. Correct Position

The practitioner’s discomfort during palpation must be avoided to ensure the accuracy of the palpation. We observe it very frequently in Medical Massage seminars when students are trying to palpate soft tissue while being in a very unfavorable biomechanical position. This simple adjustment greatly improves the work of the somatosensory system by forming and increasing correct sensory input t the brain.

To ensure quality of palpation don’t reach too far to the different parts of the body from one position. If you need to palpate the body’s opposite side, go the other side of the table. If you need to palpate along the segment, move the entire body with the palpating hand. The less distance between your body and hand(s) which conduct palpation, the less effort it causes and the more data your receptors collect.

Step 2 (Visualization). Anatomy of the palpated area and 3D visualization

The therapist must clearly understand what is under the skin in the area he or she palpates. Work on the anatomy and try to take a dissection course. It will greatly increase your professional skills.

The first part of Step 2 is having basic knowledge of the anatomy of the palpated area, which the therapist learns from anatomy textbooks or diagrams. The second part of Step 2 (Advanced) is the ability of the therapist to create a mental 3D image of the tissues in the area of palpation. Anatomy models and dissection courses are a great help. The third part of Step 2 (Advanced) is the ability of the therapist to correlate the 3D image of the palpated tissues and their relations with neighboring anatomical structures. For example, while palpating the pronator teres muscle on the anterior forearm the therapist keeps in mind the pathway of the median nerve which is located under it.

Step 3 (Visualization). Level of tissue contact

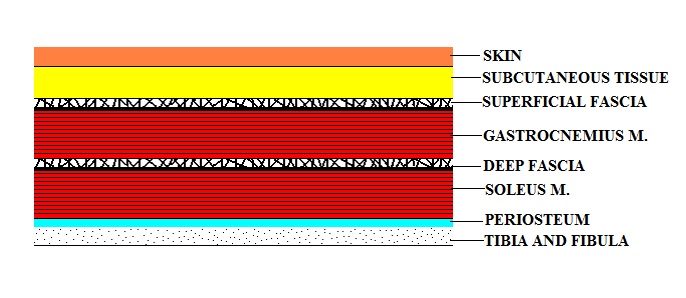

The Fig. 2 illustrates the typical soft tissue arrangement on the example of the posterior leg.

Fig. 2. Soft tissue arrangement on the posterior leg

In other parts of the body soft tissues may have one or two more layers of skeletal muscles separated by the fascia. Thus before actual palpation the therapist should have a clear vision of the desired depth of palpation. The degree and angle of pressure used during palpation depend on that.

Step 4 (Visualization). Clear identification of intentions

Before going further the therapist should have answers to following questions: “What are my intentions?” and “What I am trying to detect?” The answer to these questions is based on a successfully conducted clinical interview (see our article “The Science of Clinical Interview” in #1 Issue 2012 of JMS) and visual examination (see our article, “The Science of Visual Observation” in #2 Issue, 2015 of JMS). Only in such case the palpation becomes an informative procedure. Otherwise it is just purposelessly wondering in the tissues hoping for the accidental finds.

Step 5. Perceptual exploration

This step is the first palpatory contact with the patient. During its application the therapist detects so called qualitative components of tissues (tissue surface, first reaction to touch, changes in tissue density, elasticity, local temperature, local swelling, etc.) and quantitative components of motion (amplitude, asymmetry, and dysfunction intensity). We will discuss these issues in details in the following parts of this artcile.

Step 6. Palpatory evaluation of the movement or tissues in regard to an established reference point (Advanced)

The Video below illustrates the application of Step 6 for the evaluation of the movement. The initial goal is to examine the difference in the pelvis elevation on the affected and unaffected sides during active abduction in the shoulder joints.

First the therapist determines the positions of both iliac crests with both hands while the patient comfortably stands. Thus the therapist establishes reference points. Next the therapist asks the patient to lift both arms while he tries to detect any elevation of the pelvis on the affected side while the arms are being slowly elevated. While the patient elevates the arms the therapist tries to detect how movement affects reference points.

As readers may see in the video, the active abduction in the right shoulder joint triggers elevation of the right side of the pelvis. This picture the therapist may observe in cases of a tensed quadratus lumborum muscle.

The reference point can be also established for the soft tissue palpation. For example, during the Sensory Test, which we will discuss in the following part of this article, the therapist detects abnormalities in the skin’s innervation within affected dermatomes. To do that during the application of the test the therapist must first establish an initial reference point from which the test is conducted along or across examined dermatomes.

Step 7. Evaluation of parameters (Advanced)

This step includes the evaluation of changes in the structure of the tissues or quantitative changes in movements occurred since the last treatment session.

In part II of this article we will discuss all types of palpation and the rules of their application.

Ross Turchaninov, MD

Dr. Turchaninov graduated with honors from the Odessa Medical School in Ukraine in 1982. He was admitted to the residency program of the Kiev Scientific Institute of Orthopedy and Rehabilitation, which he completed in 1985.

After his residency, he worked as a physician at the Clinical Hospital of Department IV of the Ukrainian Ministry of Public Health.

From 1986 to 1988, he worked as a supervisor of the rehabilitation program for the Ukrainian Ministry of Public Health. During these years, he also worked with the medical team of the relief effort following the Chernobyl nuclear plant disaster.

From 1988 to 1992, Dr. Turchaninov worked as a senior scientific researcher at the Kiev Scientific Institute of Orthopedy and Rehabilitation.

In 1989, Dr. Turchaninov obtained his PhD degree in medicine, and in 1990, graduated from the Kiev Scientific Institute of Orthopedy and Rehabilitation’s manual therapy and medical massage programs designed for physicians.

In 1992, Dr. Turchaninov was invited to work in rehabilitation centers in New York City and Scottsdale, Arizona, as head of their medical massage program.

In 1998, he founded the publishing company Aesculapius Books. He lectures in the U.S. and abroad on issues of manual therapy and medical massage, and is regularly invited to speak at American and international conferences.

Dr. Turchaninov is author of more than 40 scientific papers and other publications in European and Amercian medical journals. He is author of three major textbooks:Medical Massage, Volumes I and II, and Therapeutic Massage: A Scientific Approach.

He is the founder and editor of Journal of Massage Science. Dr. Turchaninov lives in Phoenix, Arizona with his wife and daughter. His interests are literature, art, history and travel.

REFERENCES

Aubin. A., Gagnon K., Morin C. seven-step palpation method: A proposal to improve palpation skills. IJOM, March 2014, V17(1), 66-72

Jackson, P.L., Lafleur, M.F., Malouin, F., Richards, C.L., and Doyon, J. Functional cerebral reorganization following motor sequence learning through mental practice with motor imagery. NeuroImage. 2003; 20: 1171–1180

Category: Medical Massage