Massage Therapy In Cases Of Established Anti-Cancer Therapy

Dr. Jeffrey M. Cullers, DC

In Part 1 of this article published in Issue #2, 2017 we discussed the basic principles of therapy for patients with newly diagnosed cancer BEFORE anti-cancer therapy starts. The focus of Part II of this article is to share with our readers the general outlines of the massage treatment strategy for cancer patients when anti-cancer therapy (surgery, chemotherapy, radiation etc.) has already started.

Current research studies have shown that one of the primary reasons people with cancer use MT is to reduce stress, anxiety and pain (see references below). First, let’s discuss the application of full body massage for oncology patients and how the incorrectly formulated massage therapy session may negatively impact cancer patients.

FULL BODY MASSAGE

I am reminded of a student at one of our Oncology Massage Training Seminars. The woman had a five-year history of cancer, was treated with intense chemotherapy and was still taking oral cytostatic medications as a supportive therapy. She had been receiving deep tissue massage prior to being diagnosed with cancer and 5 years later was still getting deep tissue massages while her chemotherapy treatment continued.

After the seminar, she approached me and said, “Dr. Cullers, now I understand why I hurt so badly for several days after I get a deep tissue massage.”

Many cancer survivors think they can get the same full body massages with the same amount of pressure they were getting prior to being diagnosed with cancer. Unfortunately, this is a very common mistake since chemotherapy and radiation therapy besides saving the patient’s life also damage the soft tissue and circulatory and nervous systems which support them. In some cases, this damage can be irreversible. If the peripheral nervous and circulatory structures suffer during chemotherapy or radiation treatments, especially prolonged treatments, then even Swedish massage may make the patient feel worse. Deep tissue massage must be completely avoided.

Let’s now review rules of a full body massage session for the cancer patient who is going through anti-cancer therapy.

First is what not to use: Friction, percussion and compression techniques.

The skin and soft tissue of the cancer patient become very fragile because of direct damage by radiation and indirect damage by chemotherapy, which slows metabolism and kills normal cells along with cancer cells. Additionally, both therapies suppress the immune system, which makes soft tissues, especially skin, more sensitive to infection if it is damaged during friction, compression or percussion.

Thus, the therapist should concentrate on effleurage, kneading and passive stretching. First superficial and after that deep effleurage in the direction of the drainage. Any pressure must be applied only in the direction of drainage while coming back to the beginning of the stroke must be done with a feathering type of contact using fingertips, without any pressure applied to the massaged segment. As we discussed in Part I of this article, fingers and toes are reflex zones for the entire cardiovascular system and therapists should concentrate on the feet and hands, especially fingers and toes.

Kneading of skeletal muscles should be conducted using the entire palms as contact areas, with a slow pace and gentle squeeze. For superficial muscle groups, the kneading should be applied between the therapist’s hands while for the deep muscle groups the therapist should use kneading against underlining bones.

Passive stretching should be done within comfort level and only during the patient’s prolonged exhalation. Passive stretching can be done along the axis of extremity or using ROM.

LYMPH DRAINAGE MASSAGE

If surgery was performed and cancer spread to the lymph nodes, it forced the surgeon to remove them. Further anti-cancer therapy must be accompanied with regular application of Lymphatic Drainage Massage (LDM). The goal is to maintain existing drainage and eventually assist in formation of new drainage pathways via common watersheds to detour removed lymph nodes. For these patients LDM gives much more clinical benefit than regular full body massages.

If cancer didn’t spread to the neighboring lymph nodes and anticancer therapy started, the therapist should conduct several LDM sessions and later alternate them with full body massage sessions. However, if these patients developed a severe reaction to the anti-cancer therapy the therapist should use only LDM.

LDM is the most beneficial and safe way to use the MT method for cancer patients. Here are just a few of the therapeutic effects of LDM for the cancer patient, according to medical sources:

1. LDM balances the activity of the autonomic nervous system by enhancing parasympathetic tone, i.e., LDM has a sympatholytic effect (Marnitz, 1981; Bergel, 1994; Kim et al., 2009). As a result, LDM decreases stress and anxiety.

2. LDM causes an analgesic effect which is a result of the restoration of the threshold of the activation of nociceptors in the soft tissues when moderate, repetitive LDM strokes are applied (Wittlinger, 1992; Kim et al., 2009).

3. The positive effect of LDM on the immune system is well documented. It helps to mobilize and redistribute T-lymphocytes, stimulate production of natural killer cells and helps lymph nodes to work more efficiently. All of that is vitally important to cancer patients. Here are some references:

Petrov, et al. (1981) detected the increase in the number of lymphocytes in the lymph after LDM as a result of their excretion from the lymph node, as well as stimulation of their production inside the lymph nodes.

Potapov and Abisheva (1989) conducted an experimental study on 14 dogs and registered increased numbers of lymphocytes in the lymphatic system after regular application of LDM.

Groer, et al. (1994) detected an increased concentration of the immunoglobulin A in the patient’s saliva after a LDM session.

Ironson, et al. (1996) conducted an important clinical study on the effect of massage on the immune system of 29 HIV positive patients. The author registered the increased number of natural killer cells from 24.43 to 33.29 as well as the increased activity of CD8 cells from 751.77 to 821.46.

4. LDM is an exceptional treatment tool to fight post-surgical edema in cancer patients (Cheville, et al. 2003, Ezzo et al. 2015; Cho et al, 2016). However, in different clinical scenarios two protocols are supposed to be used by therapists.

If the cancer didn’t spread into the lymph nodes and they weren’t removed during the surgery, and the patient developed peripheral edema, he or she suffers from so called lyphodynamic edema. In these cases, the system is damaged by radiation and chemotherapy but the passage is still available. The application of the regularly used protocol of LDM, when strokes are directed along the lymph drainage, enhances compromised, but still functioning lymphatic pathways.

To do that the therapist frees upper lymph nodes first before draining the lower segment and lower lymph nodes into the emptied ones. These basic LDM techniques are commonly taught in the US in massage schools or in CE Seminars focused on teaching LDM.

If cancer spread into the lymph nodes and they were surgically removed there is now a physical obstacle to the lymphatic drainage since water retention is a result of direct interruption of the drainage pathways. In the areas below the surgery the patient now develops so called lymphostatic edema and basic LDM techniques we discussed above will not work efficiently if they are applied alone.

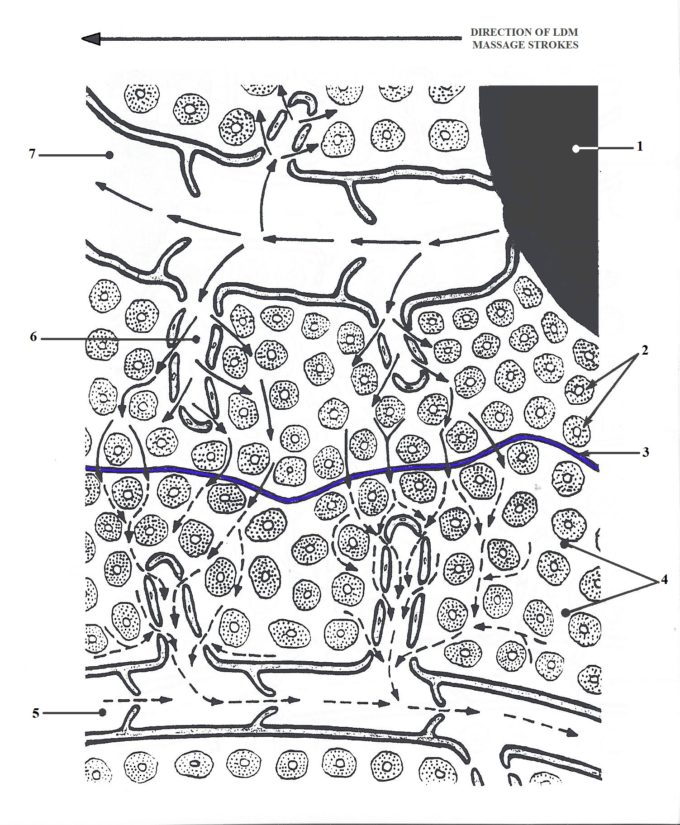

In these cases, a very special type of LDM protocol for lymphostatic edema should be used until there is at least some restoration of lymph drainage. The application of the protocol for lymphostatic edema requires a paradoxical application, since the strokes are now directed against the lymphatic drainage. This seemingly controversial idea has a very profound pathophysiological foundation. Fig. 1 illustrates events during LDM application in cases of Lymphostatic Edema.

Fig. 1. LDM application in cases of Lymphostatic Edema (Turchaninov, 2006)

1 – scar tissue in the place of surgically removed lymph node

2 – cells

3 – common watershed emphasized in blue

4 – intercellular spaces

5 – normally functioning lymphatic vessel

6 – lymphatic sac

7 – pathologically widen lymphatic vessel

Despite that lymphatic vessels are removed and they will never function again, the drainage from the neighboring parts of the body is not compromised and in many cases deep drainage from the affected areas is still working. In both cases the water retention in the form of lymphostatic edema can’t use these existing and still functioning pathways because each part of the body drains within borders of its own watersheds, which prevent exchange between two neighboring watersheds. By applying special LDM techniques in the direction opposite to the drainage the therapist increases the interstitial pressure (i.e., pressure between individual cells) and it allows edematous fluid to pass through the common watersheds and form drainage detours using still functioning pathways.

There are two schools of thought regarding LDM protocol for lymphostatic edemas. The first suggests that the protocol for lymphostatic edema only should be used until the first signs of a new detour form. The way to detect this moment is regular circular measurement of the extremity or part of the trunk before each new session. After the first signs are registered (decreased size of the measured segment) the therapist should switch to regular LDM protocol for lymphodynamic edema to enforce new drainage pathways. In the second scenario, the protocol for lympodynamic edema should be used after the protocol for the lymphostatic edema during each session. We prefer second option.

The best way for LDM to work is daily applications. To help cancer patients as much as possible while diminishing the financial burden on the family, it is very helpful if the therapist teaches the patient or member of the family to do basic LDM strokes at home between treatment sessions.

As was shown by a study conducted by an international group of scientists from the USA, Canada, Sweden and Turkey (Ezzo et al, 2015), the largest volume reduction of edema after breast surgery was registered in the group where LDM was combined with self-therapy and compression sleeves at home versus LDM + sleeves group. The therapist should conduct LDM at least two times per week.

REFERENCES

Bergel R.R. Lymphedema Therapy. The Importance of Manual Lymphatic Drainage Massage. Body Ther., Apr/May, 12-15, 1994

Cheville AL, McGarvey CL, Petrek JA, Russo SA, Taylor ME, Thiadens SR. Lymphedema management. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003 Jul;13 (3):290-301. Review.

Cho Y, Do J, Jung S, Kwon O, Jeon JY. Effects of a physical therapy program combined with manual lymphatic drainage on shoulder function, quality of life, lymphedema incidence, and pain in breast cancer patients with axillary web syndrome following axillary dissection. Support Care Cancer. 2016 May;24 (5):2047-2057

Ezzo J, Manheimer E, McNeely ML, Howell DM, Weiss R, Johansson KI, Bao T, Bily L, Tuppo CM, Williams AF, Karadibak D. Manual lymphatic drainage for lymphedema following breast cancer treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 May 21;(5):CD003475.

Groer M., Mazingo, J., Droppleman, P., Davis M., Jolly M.I., Boyton M., Davis K., Key S. Measure of Salivary Secretory Immunoglobulin A and State of Anxiety after Nursing Back Rub. Appl Nurs Rew., 7(1):2-6, 1994.

Ironson C., Field T., Scafidi F., Hashimomoto M., Kumar M., Kumar A., Proce A., Concalves A., Burman I., Tetenman C., Patarca R., Fletcher M.A. Massage Therapy is Associated with Enchancement of the Immune System’s Cytotoxic Capacity. Int J Neuroscience, 84:205-217, 1996

Kim SJ, Kwon OY, Yi CH. Effects of manual lymph drainage on cardiac autonomic tone in healthy subjects. Int J Neuroscience. 2009;119(8):1105-17.

Kurz W, Kurz R, Litmanovitch YI, Romanoff H, Pfeifer Y, Sulman FG. Effect of manual lymph drainage massage on blood components and urinary neurohormones in chronic lymphedema. Angiology. 1981 Feb;32(2):119-27.

Martinz H. Ungenutzte Wege der Manuellen Behandlung. “Karl F. Haug Verlag’, Heidelberg, 1980

Petrov P.V., Khaitov P.M., Manko V.M., Michailova A.A. Control and Regulation of Immune Response. “Nauka”, Leningrad, 1981

Potapov, I.A., Avishev T.M. The influence of Massage On Formation and Transport of Lymph. Vopr Kurortol Fiziother Lech Fiz Kult, 5, 44-47, 1989.

Turchaninov, R. Medical Massage. Volume I. Aesculapius Books, Phoenix, 2006

Wittlinger H, Wittlinger G. Textbook of Vodder’s Manual Lymph Drainage. Vol. 1, HAUG, Brussels, 1992

Category: Medical Massage

Tags: 2017 Issue #3