By Dr. Ross Turchaninov, MD

Medical Massage (MM) as a clinical modality can be successfully used to treat chronic visceral disorders. In these cases, the therapist uses reflex and local mechanisms of MM to achieve stable clinical results. The reflex mechanism of MM in cases of chronic visceral disorders was discussed in our previous article of reflex zones formation:

The local effect of MM in form of Abdominal Massage (AM) is equally and at times a critically important component of effective therapy. Thus, correctly applied AM is a priceless clinical tool for visceral disorders in the abdominal cavity. Separate protocols of AM exist for each organ in the abdominal cavity affected by various disorders.

As mentioned in the previous article, MM plays an important but supportive role in treating chronic visceral disorders. However, in some cases, MM can become a decisive clinical tool to eliminate visceral abnormality. The following two cases taken from our clinic best illustrate the value of AM.

CLINICAL CASE 1.

Approximately one year ago, a physician in our clinic started to feel heartburn-like symptoms in her epigastrium, upper esophagus, and throat. These sensations became very uncomfortable, and they interfered with her professional performance when seeing patients. The first round of testing confirmed the presence of Helicobacter Pylori in her stomach, and it was assumed responsible for causing her symptoms. She was placed on antibiotic therapy, which killed the bacteria, then confirmed by follow-up testing. Indeed, the intensity of her symptoms decreased, the heartburn in the epigastrium and behind her breastbone stopped, but sensations of severe discomfort remained in her upper esophagus and throat. A repeated H. Pylori Test was confirmed negative, and a gastric endoscopy didn’t show any signs of inflammation, ulceration, or new growth.

The patient started various medications and altered her diet to decrease acidity without success while the same symptoms persisted. The patient became very irritated, anxious, and coupled with her excessive load of patients, her quality of life significantly decreased.

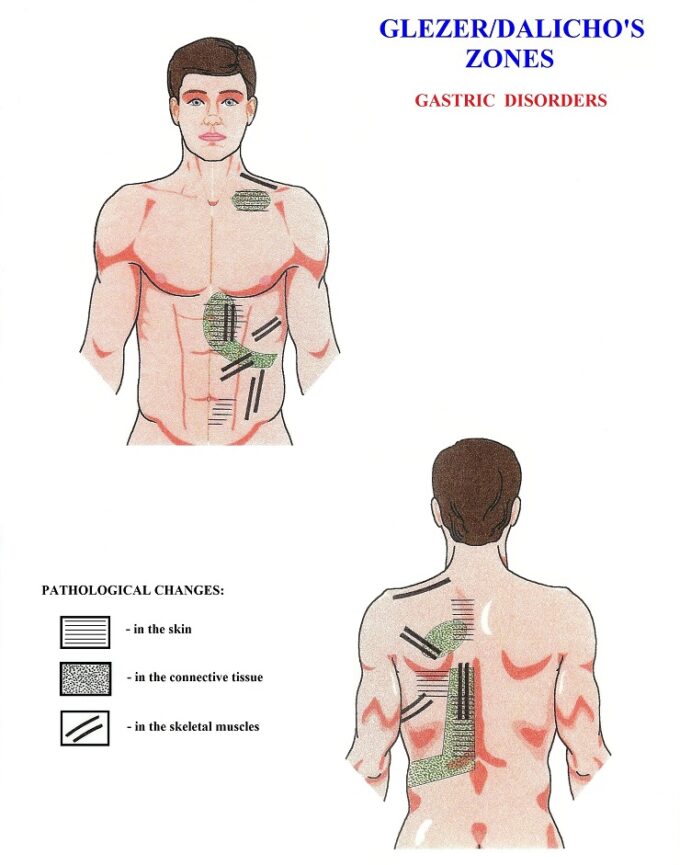

After all treatment options were exhausted, she asked if MM could offer any relief. After examination, we found that the reflex zones (according to Glezer/Dalicho zones) associated with chronic gastric disorders were active in the left middle back fascia and the erectors. There was also tension in the anterior abdominal wall, which was more prominent along the left side. Most likely, this occurred as a protective reflex signaled by the brain in reaction to the stomach’s chronic inflammation. Fig. 1. illustrates Glezer/Dalicho Zones for gastric disorders.

Fig. 1. Reflex changes in the structure of the skin, fascia, and skeletal muscles according to Glezer/Dalicho Zones for Gastric Disorders

We discussed the possibility of eliminating the reflex zones with the patient to see if the intensity of her heartburn-like symptoms would change. The first treatment session began with her positioned on her stomach. We worked on the middle-lower back to address the origin of stomach innervation and eliminate the reflex zones. Before laying down, the patient shared that the symptoms in her upper esophagus and throat were especially active. The work on her back decreased tension in the tissues and increased mobility between tissue layers. We asked the patient to roll on her back and bend her knees and hip joints so that we could work on the anterior abdominal wall to decrease the protective tension. We used LDM techniques, wave kneading, abdominal breathing counter-resistance, and other MM techniques. The patient noticed a slow decrease in the intensity of symptoms, and by the end of the first treatment session, her symptoms had dissipated. The patient was highly excited by the result of only one session, and we agreed to continue therapy in one day.

Unfortunately, the patient’s symptoms returned the following morning, and their intensity significantly increased by the end of the day. We did three daily sessions with the same immediate dissolution of symptoms and their re-surfacing the next morning. This was confusing since a disappearance of symptoms after a MM session should have a reasonable explanation.

We decided to repeat the evaluation. This time, the tension in the soft tissues in the left middle and lower back was gone entirely, but the tension in the anterior abdominal wall in the epigastrium had not changed one bit. The clinical logic here presents two most common possibilities: 1. The tension in the abdominal wall can be a soft tissue reaction to a chronic visceral disorder. 2. This tension can be a protective reaction used by the brain to guard structural changes (trauma or inflammation) in the visceral organ covered by tensed abdominal muscles.

If the patient was experiencing possibility (#1), the tension in the abdominal wall supposed to dissipate following the initial therapy exactly as tension in reflex zones in the left-middle and lower back had dissipated. However, the abdominal muscles tension remained present. If the patient were experiencing possibility (#2), the ultrasound and the endoscopy would have detected structural changes, but nothing was found. Therefore, there had to be a third scenario that triggered the clinical symptoms. The only possibility left was the presence of dysfunctional changes in the stomach itself and that was an indication to apply the AM protocol for gastric disorders.

We avoided the lower back during the fifth session and instead employed a short introductory massage to relax the anterior abdominal wall. To gain easy access to the stomach, we used the AM protocol for gastric disorders. After the session, the patient felt the eradication of symptoms and when she returned the next morning, she was still symptom-free. The patient was ecstatic because it had now been several months since she had felt heartburn-free for 24-hours. Five sessions of the AM protocol eliminated heartburn symptoms in the upper esophagus and throat, and the patient has been symptom-free for four months.

CLINICAL CASE 2.

One of our clinic’s patients brought her newlywed husband, who was experiencing severe left side chest pain that started in the early morning. The patient was in significant distress due to a family dispute the evening prior. The pain was intense, and all tests conducted in our clinic ruled out any cardiac pathology. The examining physician suspected an acute subluxation of the rib and referred the patient to our care. A complicating factor was that the patient and his wife were leaving for their honeymoon to Europe the following day.

The patient is a 28-year old athletic man with strong muscles, especially in the upper torso. He walked into the examination room slightly bent forward, keeping his right arm pressed against his left lower chest, exhibiting a slow and careful breathing pattern. He was pale, with all the visual signs of severe anxiety due to the pain’s intensity. From visual observation, he indeed exhibited all the classical signs of rib subluxation.

To our surprise, palpation along the intercostal spaces of his lower ribs in the middle back and left side didn’t trigger pain or discomfort. Palpation of the lower intercostal spaces on the anterior chest triggered moderate pain to a much lesser degree than expected in the case of rib subluxation. We began MM protocol for Intercostal Nerve Neuralgia, and as we worked along the lower intercostal spaces, the patient exhibited no discomfort. We purposely increased the intensity of therapy, and the patient still didn’t experience pain. When we asked him to roll onto his back, it took him a while to do so, and he immediately bent his knees and his hip joints to ease the intensity of pain. As soon as we began to work along the lower edge of his rib cage, the patient groaned with pain and began to sweat.

The lower edge of the rib cage, especially in the epigastrium, is the insertion site of the abdominal muscles that form the anterior abdominal wall. We, therefore, decided to examine this part of the body in detail. Indeed, the anterior abdominal muscles felt as stiff as a board, and the patient exhibited significant discomfort during even mild palpation. Considering our lack of time and the patient’s next day travel plans, we decided to concentrate on the anterior abdominal wall instead of the lower intercostal spaces. We began with very gentle effleurage strokes in an inhibitory regime along the rectus abdominis muscles, eliciting a gradual decrease of protective muscle tension. The board-like anterior abdominal wall now started to slightly cave in, as it would in an average person laying on their back. After the tension in the rectus abdominis subsided, the patient felt some relief in the pain’s intensity, and he immediately put both extremities flat.

We decided to slightly increase the effleurage strokes’ depth and follow the gastric musculature’s orientation. At this moment, the most bizarre event of my professional life occurred: the patient’s abdomen produced an extremely loud, almost surreal groan, and the entire epigastrium started to move and roll as if an alien was moving inside the patient’s abdomen. For a second we were both petrified by the sound and what we were seeing. As soon as the anterior abdominal wall in the epigastrium stopped moving, the patient visibly relaxed, sat upright, and got up without any pain. We kept him in the clinic for half an hour for observation, and the next day he flew to Europe with his wife and hasn’t had similar problems since.

DISCUSSION

What happened to these two patients, and why did AM make such a dramatic impact on their lives? Both patients had the same problem despite differences in their clinical pictures. For context, let’s briefly review the anatomy and physiology of the stomach. The stomach’s primary function is to produce acidity to kill any pathogens that enter the body with food and mix gastric juice with that food to break down fat and large protein molecules into smaller pieces. Afterward, this gastric content moves to the intestine, where further food processing and nutrition absorption occurs. Thus, physiologically speaking, the stomach’s two main jobs are the secretion of gastric juice and the peristalsis, or mixing, of gastric content.

In this context, the gastric motility of peristalsis is more important. The walls of the stomach consist of three layers of smooth muscles, which run in three different directions to the main axis of the stomach: 1. Outer, longitudinal layer. 2. Middle, circular layer. 3. Inner oblique layer (see Fig. 2).

1 – outer longitudinal layer of smooth muscles

2 – middle circular layer of smooth muscles

3 – inner oblique layer of smooth muscles

Such arrangement allows for the optimal mixing of gastric juice with newly arrived food. Both parts of the autonomic nervous system are equally responsible for gastric peristalsis: the parasympathetic system via the vagus nerve and the sympathetic system via the spinal nerves from T5-L3 spinal segments. Normal peristalsis is a result of the precise coordination in the contraction of all muscle layers. Loss of coordination triggers various consequences: delay in, or speedy evacuation of gastric content into the duodenum, increased acidity, insufficient fat emulsification etc.

Both patients’ main trigger was increased sympathetic nervous system activity due to excessive stress (the number and complexity of patients our physician was dealing with, and a family fight the evening before for our second patient). A significant increase in sympathetic tone disrupted the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems resulting in layers of smooth muscles losing their coordination and severely impacting gastric peristalsis.

However, from this point, things developed differently for both patients. For the first patient, all stomach muscle layers got tighter and as a result peristaltic waves got shorter but they were still present. Tension in the gastric muscles increased the inner pressure within the stomach cavity, and acidic gases began to escape into the esophagus via the esophageal sphincter. Therefore, the patient felt heartburn in the upper esophagus and the throat rather than the usual place for heartburn behind the breastbone when gastric content enters the lower esophagus via a failing esophageal sphincter. AM released tension within the stomach’s walls, decreased the inner pressure in the stomach and prevented stomach gases from escaping into the esophagus. This eliminated her heartburn symptoms in the upper esophagus and the throat. Knowing now that stress at work was the cause of her symptoms, our physician started to control her stress level during work hours. With the addition of monthly AM sessions, she was able to eliminate any residual symptoms.

Triggered by a family dispute, the second patient’s increased sympathetic tone, created such discoordination in the peristaltic waves that the layers of smooth muscles ‘stuck.’ In this patient the peristaltic waves almost completely ceased, creating acute pain in the epigastrium, radiating to the lower chest and mimicking a rib subluxation. The restoration of normal peristalsis using AM techniques was such a violent event stunning both patient and therapist but it immediately eliminated all symptoms since peristaltic waves were now normalized.

For therapists who may experience similar cases, we would like to share a simple application of AM for gastric disorders. As with any MM protocol, the technical application is simple, but the therapy’s place, depth, and orientation are critical factors.

The therapist should start with several minutes of LDM to decompress the fascia and rectus abdominis, followed by wave kneading of the abdominal muscles in an inhibitory regime and abdominal breathing resistance techniques. Afterward, therapists can employ AM techniques (10-15 min) to restore normal gastric peristalsis while the patient keeps their lower extremities flexed in the knees and hip joints to decrease pressure in the anterior abdominal wall. Here is protocol of AM. Entire session of AM should not exceed 10 min and entire therapy should be done within the patient’s comfort zone. Fig. 3 illustrates area of AM’s application

Fig. 3. Area of epigastrium

Black lines – edges of the rib cage

Red lines – area of epigastrium for AM

- Superficial and deep effleurage along each muscle layer in the patient’s epigastrium

- Aligned Friction along and across fibers of each smooth muscle layer. Notice the correct placement of the passive hand’s base (in cup-like arrangement), alignment of the fingertips in one line, and careful and slow bi-manual submergence of the fingertips into the epigastrium, during the patient’s exhalation. The Aligned Friction used only while abdominal wall is relaxed, i.e. during the exhalation.

- Repeat effleurage strokes

- Therapy can be finished with a short 1-2 minute application of mobile electric vibration over the epigastrium and along the food passage.

Category: Medical Massage

Tags: 2021 Issue #3