By Dr. Ross Turchaninov, MD

My colleague B. Prilutsky suggested that the Journal of Massage Science should publish article on Periostal Massage (PM). Once, we addressed that subject in Massage & Bodywork Magazine but it was many years ago and massage science has developed further since then.

The basic principles of Periostal Massage were developed in Germany by two physicians Dr. Vogler, MD and Dr. Krauss, MD. After years of clinical observations, Dr. Vogler and Dr. Krauss concluded that the periosteum, besides playing a critical role in the normal functioning of our skeleton, is greatly affected by chronic somatic and visceral disorders forming so-called periostal reflex zones. They in turn start to further complicate the initial somatic and visceral disorders. Thus Dr. Vogler and Krauss developed PM as a clinical tool to restore normal function to the periosteum, eliminate periostal reflex zones and help patients to recover sooner. In this Part I we are going to discuss the periosteum and its important functions in the human body.

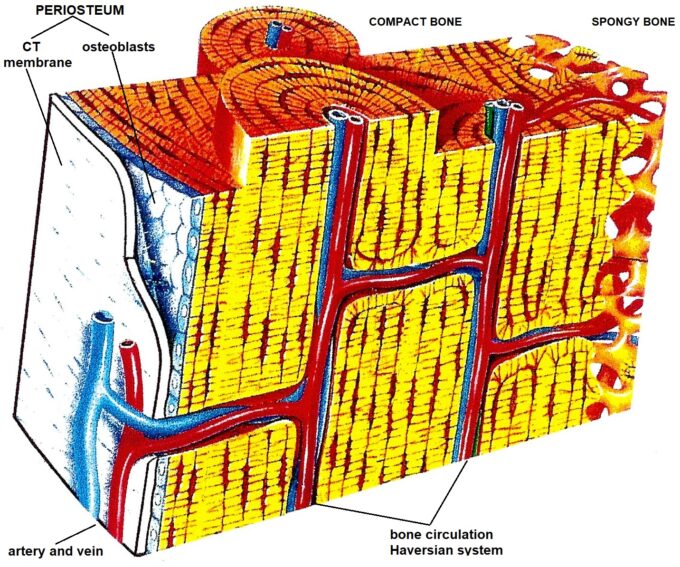

There are five types of soft tissues: skin, fascia, skeletal muscles, tendon and ligaments, and periosteum. The periosteum is a thin membrane (2-3 millimeters) that consists of two layers: outer and inner. Outer is a connective tissue membrane similar to the strong fascia. Inner is one single layer of cells called osteoblasts. The periosteum covers all bones, and it borders the cartilage which covers joint surfaces. Fig. 1 illustrates the anatomy of periosteum.

Despite that, the periosteum looks like an ordinary let’s say less important type of soft tissues The perisoteum is everything for the bones. Without periosteum we are not going to have a stable skeleton and simply are unable to survive. Let’s first enumerate on the critically important functions of the periosteum:

1. Bone Circulation

2. Bone Innervation

3. Support of Locomotion

4. Bone Remodeling

Let’s review these important functions of the periosteum in detail.

BONE CIRCULATION

The entire bone circulation consumes approximately 10% of cardiac output and it works under high pressure since the blood must enter such resistant tissue such as bone. The bone circulation is called the Haversian system. This network of arteries and veins spread throughout the entire periosteum which covers the bones and enter the inner bone via the so-called nutrient foramen. Fig. 1 illustrates bone circulation and the role that the periosteum plays in it.

BONE INNERVATION

As with all tissues and organs, the periosteum has sophisticated innervation. In reality, when we are talking about a bone’s innervation, we are actually talking about the innervation of the periosteum which covers all bones. When we fracture any bone, the horrible pain we experienced is not coming from the fractured bone but rather from damaged periosteum. Thus, all nociceptors as well as all other sensory receptors are located in the periosteum but not in the bone itself.

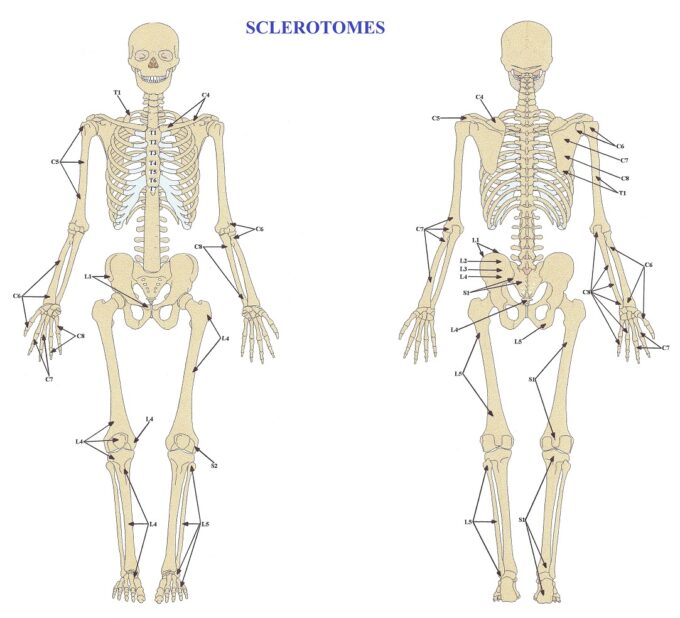

Similar to the skin, skeletal muscles and other tissues and organs there is clearly have an established pattern of periosteum’s innervation by different segments of the spinal cord. This pattern of innervation is called the sclerotomes map and it was published in 1944 by Dr. V.T. Inman and Dr. I.B. Saunders. Fig. 2 illustrates a map of the sclerotomes map (Inman and Saunders, 1944).

From the clinical perspective, these maps are a very important somatic evaluation tool, and each therapist must use them daily. We will discuss this important issue in the next parts of the article.

SUPPORT OF LOCOMOTION

All the soft tissues which support the body’s dynamic and static functions insert into the periosteum. This includes tendons that support muscle contractions and ROM in the joints, ligaments that provide joint stability, and the joint capsules which support their normal functions inserted into the periosteum which itself is very firmly attached to the bones. Thus, the periosteum is a key stabilization component of our locomotion. Its trauma or even mild inflammation deeply affect the function of the affected segment(s) affecting a range of motion and eventually the formation of different adhesions. Fig. 3 illustrates how fibers of the periosteum growing into the bone for the better stabilization of the muscles, ligaments etc.

BONE REMODELING

Fractured bone can’t repair itself and reconnect fragments. This critically important healing mechanism is completely under the control of the periosteum. One layer cells which form the inner layer of the periosteum are responsible for the new bone formation and fracture union.

These cells (see Fig. 1) which called osteoblasts immediately activated when periosteum is damaged during a bone fracture or bone inflammation. As soon as osteoblasts are active, they start to produce pro-collagen which they unload in the area of bone trauma. Within the line of fracture, the pro-collagen matures into collagen fibers and later calcium and phosphorus are deposited there triggering the collagen ossification and that finishes fracture healing. That is why we need stabilization of the fractures and complete rest to let periosteum to finish its job and make us mobile again after severe trauma.

The bone remodeling function of the periosteum has its own drawbacks. The formation of bone osteophytes that accompany Osteoarthritis is an example of the negative side of remodeling function of the periosteum. We will discuss this issue in detail in Part II of this article.

Thus, as you see bones of our skeleton are dead if periosteum is not present and the function of the skeleton is greatly affected if the periosteum is damaged or malfunctioning.

Join Science of Massage Institute for Medical Massage Seminar in Phoenix, AZ on August 27-29. To learn more please click here: Medical Massage Courses & Certification | Science of Massage Institute » Phoenix, AZ August 27-29, 2022

REFERENCES

Inman V.T., Sauders I.B. Referred Pain from Skeletal Structures. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis., 99, 660-667, 1944

Vogler, P., Krauss, H.: Periostbehandlung. Leipzig, 1953

Category: Medical Massage

Tags: 2022 Issue #1