By Dr. Ross Turchaninov,

Phoenix, AZ

We have published three parts of this article in the previous issues of JMS. To review them, please use these links:

Now it’s time to discuss the primary treatment option for periosteal dysfunctions – Periostal Massage (PM). We will use Tennis Elbow, or the medically correct term – Lateral Epicondylitis, as an example of PM application. The same therapy principles apply to similar pathological conditions, such as Golfer’s Elbow, Styloiditis, Osteoarthritis, Tibial Compartment Syndrome, Achillodynia, Sacroiliitis, etc.

As stated, dysfunctions are formed in areas where soft tissues insert into the periosteum as major stabilizations points, which are covered only by skin. Since the periosteum is a richly innervated membrane, even its microscopic trauma or detachment from the bone causes various dysfunctions.

The ultimate clinical solution for TE and similar abnormalities is to re-attach the periosteum to the bone and re-enforce it for future stability – precisely what PM is designed to do.

First, let’s review the options a patient with acute Tennis Elbow currently has:

1. A family physician will prescribe pain medication, anti-inflammatories, muscle relaxants, ice therapy, and rest with an elbow brace – all of which will fail in the majority of clinical cases.

2. A PT will use various modalities, including light repetitive exercises, to temporarily alleviate the problem. (Hoogvliet et al., 2013). Very frequently light repetitive exercise will additionally inflame and detach the periosteum.

3. A DC will manipulate bones that form the elbow joint, but since soft tissue is not addressed, such therapy provides only a partial solution (Hoogvliet et al., 2013).

4. A steroid injection will dramatically help the patient to cope with pain and inflammation but does not re-attach the periosteum. The same symptoms of pain and dysfunction will return in 67% of patients within one to six months (Troisier, 1991; Verhaar et al., 1996)

5. Surgery is the only solution if trauma to the periosteum is severe and 75% or more tendon or ligament fibers are detached. However, this will only serve a minority of patients, especially with a recent clinical diagnosis of TE.

All these therapies are better considered after PM fails to deliver stable clinical results.

Next, let’s review cellular events at the site of periosteal dysfunction. Any inflammation or trauma in the soft tissues and inner organs must be repaired, involving different factors. First, macrophages and neutrophils clean out debris and remnants of the initial injury. The next step in healing the periosteum is activating fibroblast cells at the site of injury or inflammation and attracting more fibroblast cells if needed. A major healing and rebuilding force in the human body, fibroblasts are directly responsible for forming scar tissue, for example, when we cut our skin with a knife. Similarly, they help the cardiac muscle to heal after a heart attack and fill the cavity formed in brain tissue after a stroke.

When tissues and organs don’t need repair, fibroblasts are inactive or dormant, comprising entirely different cells called fibrocytes. Fig. 1 illustrates a microphotograph of a fibrocyte.

Fig.1. Fibrocyte (microphotograph)

Fibrocytes must come out of dormancy to repair tissue and organ injury or trauma. Fibrocytes are transformed into fibroblasts when damaged or inflamed tissue release histamine into extracellular space at the site of damage or inflammation. As soon as local histamine concentration increases, the special receptors with a strong affinity for histamine located on the outer membrane of fibrocytes bring these cells from the dormant state, transforming them into entirely different cells called now fibroblasts.

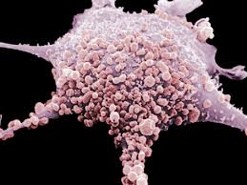

Fibroblasts even look different because they are larger, and more critically, fibroblasts acquire legs, allowing them to move within the tissues and organs. Fig. 2 illustrates a microphotograph of a fibroblast.

Fig. 2. Fibroblast (microphotograph)

Here is the fascinating part! There may not be enough fibroblasts at the injured or inflamed site, so fibroblasts from neighboring and even non-injured areas must be employed to complete the repair.

How do fibroblasts know where to go? They use the same histamine-sensitive receptors on their outer membrane as GPS. Let’s say that moving fibroblasts moved away from the shortest path to the area of injury. When that happens, the concentration of histamine will drop, and receptors will immediately pick up that information, guiding fibroblasts to the route where the concentration of histamine is highest. This mechanism brings fibroblasts to the areas where they are most needed.

After fibroblasts arrive at the site of the largest concentration of histamine, i.e., the site of the injury, they produce a protein called pro-collagen. This protein is uploaded into the tissues or organs, maturing into fully functioning collage fibers and forming scar tissue. As mentioned previously, this can be the scar formed on the skin after a knife cut or in the cardiac muscle of a patient who survived a heart attack, as has been detected by ECG.

Why are periosteal dysfunctions so challenging to treat, and why do they tend to recur? On the one hand, the area of inflammation and trauma is tiny, sometimes only 2-3 mm, and there is not enough histamine released from the affected area. A lower concentration of histamine in an injured area equals a smaller number of fibroblasts working there to repair the injured periosteum. On the other hand, the affected area of the periosteum has very thin, soft-tissue coverage, preventing effortless movement of fibroblasts to the injured site. Because the patient still needs to drive, type, etc., the amount of pro-collagen deposited in the soft tissue by fewer fibrocytes working there is easily destroyed by muscle contractions that support our daily activities. From that perspective, the amount of pro-collagen must be dramatically increased. In such cases, some pro-collagen continues to be destroyed, while other pro-collagen will have a chance to mature into collagen fibers. Layer by layer, deposits of collagen fibers will solve periosteal dysfunction. This can happen only if the number of fibroblasts working at the injured site significantly increases.

Thus, the primary goal of PM is to restore healthy function by activating and attracting a maximum number of fibroblasts to the injured or inflamed site. In the final part of this article, we will discuss the rules of PM application.

REFERENCES

Hoogvliet P., Randsdorp M.S., Dingemanse R., Koes B.W., Huisstede B.M.A.Does the effectiveness of exercise therapy and mobilization techniques offer guidance for the treatment of lateral and medial epicondylitis? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2013 Nov;47(17):1112-9

Troisier O. Tennis Elbow. Rev.Prat. 1991, 41(18).

Verhaar J.A, Walenkamp G.H., van Mameren H., Kester A.D., van der Linden V.A. Local Corticosteroid Injection Versus Cyriax-type Physiotherapy for Tennis Elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1996 Jan; 78(1):128-32

About the Author

Dr. Ross Turchaninov

To read Dr. Ross Turchaninov’s Bio please click here: Medical Massage Courses & Certification | Science of Massage Institute » Editorial Board

Category: Medical Massage

Tags: 2023 Issue #1