Our former student, Brenda Howell, LMT, CMMP, opened the Institute for Massage and Bodywork Therapy, a massage therapy school in Fayetteville, NC. This school represents new advances in MT education with a curriculum based on massage science and its clinical applications. Although the school is relatively young, it has already generated raving reviews and support from businesses and the medical community that hire its newly graduated therapists because of their impressive technical skills and clinical abilities.

To illustrate her school’s achievements, Brenda sent us two clinical cases written by her students, Jaci Stephens and Julia Shackelford. In this issue, we will publish Jaci Stephens’ contribution. We want to emphasize that Jaci was still a student in MT school at the time of submission! However, Jaci obtained exceptional theoretical knowledge and technical skills thanks to Brenda’s and other instructors’ teaching and expertise.

Notice that the school requires students to collect and interpret clinical data correctly. Thus, this clinical case is a perfect example of effective MT education based on science rather than personal opinions and anecdotic experiences. Finally, Jaci illustrated how soft tissue evaluation must be done by therapists who work in the clinical setting.

We are very proud that SOMI training allows therapists to help patients in very complex clinical situations and that our former students can share their expertise with new therapists.

Dr. Ross Turchaninov, Editor-in-Chief

MEDICAL MASSAGE vs MULTI-LAYERED SOMATIC PATHOLOGY

Jaci Stephens, MT Student

Medical Massage Class IMBT 2023

General Information

The patient is a 43-year-old woman who has an office job. She presents with left-side chronic ear pain and headaches, which have been ongoing for over a year. The patient also complains about tension down the left side of her neck and into her shoulder.

Initially, she suspected an ear infection and visited an ENT doctor, who reassured her that there was no ear infection, so no medications were needed. Instead, the physician concluded that musculoskeletal dysfunction was the cause of her symptoms and recommended that she see a somatic specialist. The physician did not perform imaging or further testing.

The patient’s office work and poor ergonomic situation may contribute to her symptoms. She did not have prior neck or head trauma.

Initial Complaints

At the time of evaluation, the patient complained about mild tension in her left neck. However, she had taken ibuprofen roughly 5-6 hours prior, and she takes NSAIDS daily to address her pain and discomfort. She has been getting full-body relaxation massages twice a month since June and noticed some decrease in intensity. However, this relief typically only lasts 3-5 days after the massage, when her symptoms return to the previous intensity.

The patient describes those symptoms as tension that starts as dull and aching, then compounds over time until it peaks as a sharp pulsating pain. On a scale of one to ten, the intensity of her pain can reach seven. At the time of evaluation, she described her symptoms as tension rather than pain.

Usually, when an attack starts, it originates around the left ear and radiates to the left neck all the way to the top of her left scapula. At the peak of pain, it creates a compressive band of tension and pain around the entire head. She notices feeling ‘off-kilter’ when the intensity of ear pain increases. She doesn’t have an aura before a headache attack.

The patient notices more tension, stiffness, and pain in the morning. At night, she sleeps on her left side because sleeping on the right side triggers the sensation of a ‘pull’ on her left neck and upper shoulder. She places her right leg in a hiking position and uses support pillows for additional comfort.

Assessment

Visual Evaluation

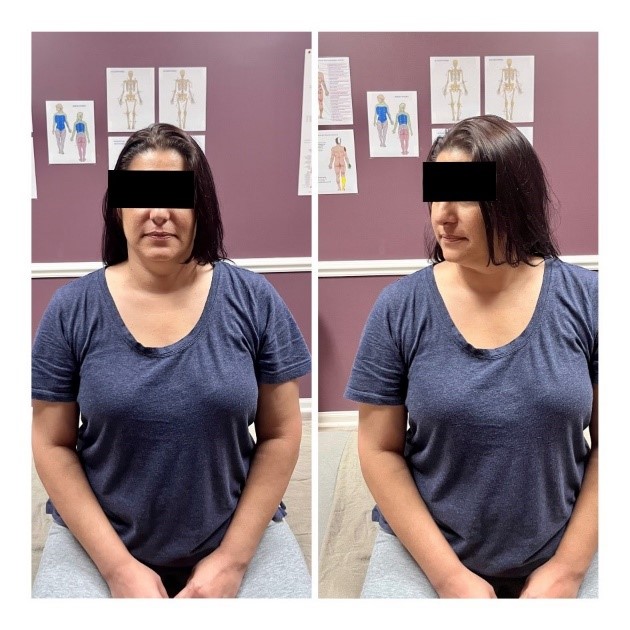

The patient exhibits moderate kyphosis, and shoulders are rolled forward. Evaluation of active ROM in the neck shows significant restrictions. She can only rotate her head to the right a few degrees without pain. Further rotation to the right triggers pain in the left neck and ear. She must rotate her upper body to look over her right shoulder without pain. Rotation to the left is almost within normal ROM. Fig. 1 illustrates her ROM during rotation to the right. Further rotation triggers pain in the left neck and shoulder.

Lateral flexion to the right (ear-to-right shoulder movement) is also limited and triggers pressure and pain in the left neck and ear.

The neck’s flexion (drawing the chin to the chest) is very limited, and this movement immediately triggers sharp cervical pain, specifically in the C5-C7 area. Fig. 2 illustrates ROM in cervical flexion.

Interpretation of Obtained Data

Given the acute onset of pain without injury or trauma, it is most likely due to the phenomenon of hyperirritability, and this has been building for some time without the patient necessarily noticing anything of concern. While I suspect some incorrect postural habits and perhaps muscle imbalance, her clinical symptoms certainly are the compensatory reactions to hyperirritability of peripheral receptors. With this in mind, I fully expect to find reflex zones, trigger points, and hypertonus during palpatory evaluation. This also explains why she experiences a degree of relief after relaxation massages.

My evaluation of the patient’s pain indicates that her dull, aching pain, which increases with active movement, is more likely an indicator of active trigger points and/or myogelosis. The sharp pain triggered by neck flexion indicates potential irritation of the cervical spinal and/or peripheral nerves.

The pulsating pain she sometimes feels around the ear is more likely associated with acute inflammation in the occipital nerves irritated by over-tensed soft tissues in the posterior neck.

Evaluation of Sensory Deficit, Dermographism, and Reflex Zones

Using the Glezer/Dalicho zones for cervical, thoracic, and Lumbosacral Spondylosis as a reference, I evaluated sensory deficit and dermographism reactions. During the Sensory Test across dermatomes in the patient’s back (striking the skin along both paravertebral lines), the patient reported less sensation on her left side. The second set of lines created stayed red longer bi-laterally and were a little more pronounced on left side. This indicated a mild imbalance within her autonomic nervous system.

I also referenced the Glezer/Dalicho’s Zones when I examined the patient’s connective tissue reflex zones of the first and second levels (in the skin and superficial fascia). I used Keibler’s and Dickle’s techniques to assess the presence of reflex zones there. Overall, the tissue density appeared similar bilaterally; however, there were several areas where mobility of the soft tissues was restricted on each side.

Interpretation of Obtained Data

It’s important to note that the patient received regular relaxation massages focused on the upper back. I suspected this work helped to reduce symptoms within the cutaneous reflex zones and to balance her autonomic nervous system.

However, the results of the Sensory Test indicated that the spinal nerves supplying affected dermatomes were irritated. From a treatment perspective, I considered that decompression of the fascia and paravertebral muscles was needed to free cutaneous branches of the affected spinal nerves from irritation. I added Connective Tissue Massage (CTM) to the treatment protocol for this purpose.

Further Testing

I used the Cervical Compression Test (CCT) to examine the degree of pressure within cervical vertebral segments, which may irritate spinal nerves. With the patient seated upright, her head in a neutral position, and looking forward, I applied pressure on top of the head during prolonged exhalation. As soon as I applied moderate vertical compression on the patient’s head, she felt an electrical-like tingling sensation on the left side of the neck at the level of C6-C7 with some radiation of pain down her left shoulder.

I next performed Wartenberg’s Test to rule out or rule in compression of the brachial plexus by anterior scalene muscle. The patient was seated upright and I applied pressure above and behind the middle portion of her left clavicle, using my thumb placed flatly. The Wartenberg’s Test was negative.

Next I used Zaslavsky’s Test. The patient placed an arm behind her back as far as possible, then added forearm pronation and held it for 15 seconds or until pain or tension presented (or increased). This was positive on her left side. While trying to put an arm behind her back, she was forced to elevate her shoulder and rotate it forward (her left scapula slightly wings) while she did the test. Also, she noted pain within a few degrees of pronation and, after that, started to feel fasciculation and twitching in her hand.

Grinstein’s points on the top of the patient’s head were positive on the left as the patient experienced tension and a stinging sensation with even mild compression of the cranial aponeurosis. Positive Grinstein Points indicated the presence of significant tension and restrictions in her cranial aponeurosis. Further examination of the scalp detected several areas of tension within the left side of the cranial aponeurosis, near the coronal suture, temporal line, and lambdoid suture.

The Compression Test (CT) for evaluating the greater and lesser occipital nerves indicated that even mild compression elicited an immediate and intense pain response. The patient mentioned the pain felt the same as with a headache. I used CT separately on:

- Above occipital ridge – positive CT meant that tension in the occipitalis muscle irritates the greater occipital nerve.

- On the occipital ridge – positive CT indicated that tension at the insertion of the trapezius to occipital ridge is irritating her greater occipital nerve.

- Below occipital ridge – positive CT indicated that tension in the splenius capitis is irritating her greater occipital nerve.

- Behind mastoid process – positive CT indicates irritation of the lesser occipital nerve.

Testing of posterior cervical muscles indicated the presence of active trigger points in her trapezius, levator scapula, and splenius capitis. There was tension in the left semispinalis capitis as well.

Interpretation of Obtained Data

The positive CTs confirmed significant tension in the posterior cervical vertebrae. It seemed this was the root of her symptoms and needed to be addressed by matching the Medical Massage protocol. Based on the results of Zaslavsky’s Test and Trigger Point Tests, I decided to concentrate on the left trapezius and right levator scapula muscles. The tension detected during the cranial aponeurosis examination also suggested including Scalpotherapy in future protocol.

The positive CTs furthermore indicated the greater and lesser occipital nerves entrapped in suboccipital space on all levels, starting from the obliques capitis superior to occipitalis muscles. I planned to free those nerves from irritation by the trapezius, semispinalis capitis, and the obliques capitis superior muscles.

TREATMENT

Design of Medical Massage Therapy

Our student clinic is only open on Saturdays, so sessions are limited to once a week. These results are from one month of work over 4 hour-long sessions. I chose to start our sessions with a combination of the following Medical Massage protocols:

- Chronic Headache

- Trapezius Muscle Syndrome

- Levator Scapulae Muscle Syndrome

I considered further alterations to my treatment plan depending on the patient’s progress.

Session 1

During the first Session, I focused heavily on an inhibitory regime of massage therapy to address the soft tissues in the posterior neck. I used a combination of effleurage, friction, kneading, passive stretching, and techniques to relax the cervical and thoracic paravertebral muscles. I worked layer by layer and used steps from the Medical Massage protocols I mentioned above. I also did introductory work in the suboccipital space and finished with applying Scalpotherapy.

Session 2

After the first session, the patient had mild swelling and tenderness in her posterior neck and upper back (especially from C6-T2) for two days, an expected reaction to the first treatment session. I used the same treatment frame but concentrated on the suboccipital space and scalp. At the end of this session, the lateral flexion in her cervical spine significantly improved.

Session 3

No headache for a week! Evaluation at the beginning of this session demonstrated that the Cervical Compression Test became negative, while Zaslavsky’s (left side) was still positive. I also included C-tests for the axillary nerve and pronator teres muscle syndrome, which were positive on the left. With this in mind, I added steps of the Anterior Scalene Muscle Protocol to the session and Trigger Point Therapy enforced by electric vibration to deactivate trigger points in the trapezius, levator scapula, splenius capitis, and semispinalis capitis muscles. I gave the patient further instructions on how to use foam rollers at home, address glutes, and roll up along the paravertebral lines to maintain the progress of the therapy.

Session 4

During session number four, I noted the presence of tension in the left subscapularis muscle and still some signs of axillary nerve irritation. I repeated the treatment protocol from the previous session, adding more work on the anterior scalene muscle and subscapularis muscle. I also worked briefly on her lumbar spine on the left.

RESULTS

Of course, four sessions of MM therapy were not enough to resolve all aspects of the patient’s pain and dysfunction. However, after these sessions, the patient reported:

- Only residual pain around the left ear.

- No pain but rather tension in the left neck.

- No headache after the second session.

- An increase in cervical ROM, residual tension with cervical flexion, and lateral flexion.

- An improvement in cervical rotation.

Besides the Cervical Compression Test, which was negative, the degree of Zaslavsky significantly improved. Fig. 3 illustrates the results of Zaslavsky’s Test before and after the treatment. In the right picture, the patient exhibits full rotation, no winging of the left scapula, no elevation of the left shoulder, and minimal forward rotation in the left shoulder.

The patient’s bright personality has shown up more in the last three sessions. We followed her monthly after the end of the Medical Massage therapy, and she hasn’t had any headaches since there is only mild tension in the left neck.

SOMI is looking for clinically oriented therapists who would like to enter the professionally exciting field of Medical Massage. We will clinically train therapists using only scientific data until you become independently thinking Massage Clinicians! Join Science Of Massage Institute!

Here are the links to the SOMI’s Medical Massage certification Program:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jaci began her career helping people through sports nutrition in 2016. She currently holds a certification in nutrition through the American Sports and Fitness Association. Wanting to help her clients even more, she pursued her massage therapy license in 2023 and graduated at the top of her class from the Institute for Massage and Bodywork here in Fayetteville, NC.

Experiencing two complicated pregnancies and several sports-related injuries, Jaci knows how impactful therapeutic massage can be on someone. She is passionate about learning Medical Massage and improving the quality of life of everyone who gets on her table.

Category: Case Studies

Tags: 2024 Issue #1