by Dr. Ross Turchaninov

In Part I of this article, Medical Massage Courses & Certification | Science of Massage Institute » TREATING THE PAIN IS CHASING THE TAIL. PART we reviewed the initial and critical components of the pain-analyzing system—specifically, the normal and abnormal function of various peripheral receptors located in soft tissues and inner organs affected by different pathological conditions, including trauma.

Part II is dedicated to the function of nociceptors (also known as pain receptors), which initiate the activation of the pain-analyzing system.

NOCICEPTORS (a.k.a Pain Receptors)

Another name for Nociceptors (NC) is free nerve endings. They were first described in 1906 by Dr. C. S. Sherrington. NCs are non-encapsulated receptors and serve as the starting point of the pain-analyzing system. Their lack of an encapsulated structure reflects their evolutionary age—they belong to a very ancient sensory-control system.

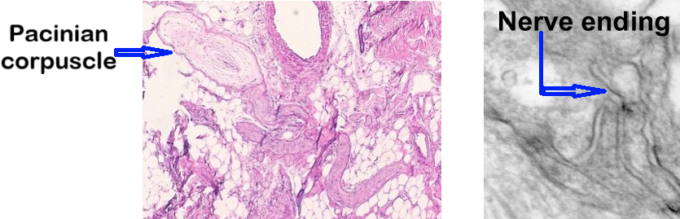

Microphotographs in Fig. 1 illustrate the comparative anatomy of a Pacinian corpuscle (a receptor specialized for vibration detection) and an NC-free ending. As the image shows, the Pacinian corpuscle has a clearly visible capsule, whereas the NC appears as branching nerve endings without an enclosing capsule.

NCs share structural similarities with other mechanoreceptors, but they differ significantly in their rate of adaptation. Some NCs are rapidly adapting, whereas the majority are adapting slowly. This concept is vital for any practitioner of Medical Massage based on clinical science.

The receptor’s rate of adaptation directly influences how the patient’s brain forms clinical symptoms. These symptoms are what bring patients to the clinic, and therapists must understand how they develop—and how to address them effectively.

Slowly Adapting NCs

Most nociceptors belong to this group. After tissues are exposed to a damaging stimulus, NCs immediately transmit signals to the CNS, where pain perception is formed. With slow adaptation, the number and frequency of signals sent to the CNS do not decrease as long as the noxious stimulus remains. In other words, NCs continuously signal to the brain ongoing danger.

Rapidly Adapting NCs

These receptors respond to initial exposure to mild noxious stimuli, but if the stimulus is repetitive and not truly harmful, they soon stop firing. As a result, the initial pain sensations diminish and eventually disappear. Activation of rapidly adapting NCs is one of the initial clinical goals of Medical Massage therapy to help regulate and calm the pain-analyzing system.

NCs in ACUTE and CHRONIC PAIN

Above the level of NCs, the pain-analyzing system comprises two equally important components: the FAST and SLOW pain-analyzing systems. The difference between them lies in the speed at which electrical impulses are conducted from NCs to the CNS. This speed depends on whether the nerve fibers are myelinated (fast pain) or unmyelinated (slow pain).

- Fast pain system → responsible for acute pain sensation formed by the CNS

- Slow pain system → responsible for chronic pain sensation formed within the CNS

When we touch a hot surface, withdrawal is immediate. This basic reflex arc is governed by the fast pain system, largely contained within the spinal cord with minimal involvement from the brain:

Noxious stimulus (e.g., extreme heat)→ NC activation → spinal cord → acute pain → motor response (we jump from the source of heat)

In contrast, the formation and conscious recognition of chronic pain involve full participation of the patient’s brain. Chronic pain is mediated by the slow pain system (Marchettini et al., 1996; Ochoa & Torebjörk, 1989). A classic clinical example is Fibromyalgia, where chronic pain becomes widespread and persistent.

DERMATOMES AND THE ORGANIZATION OF NC INPUT

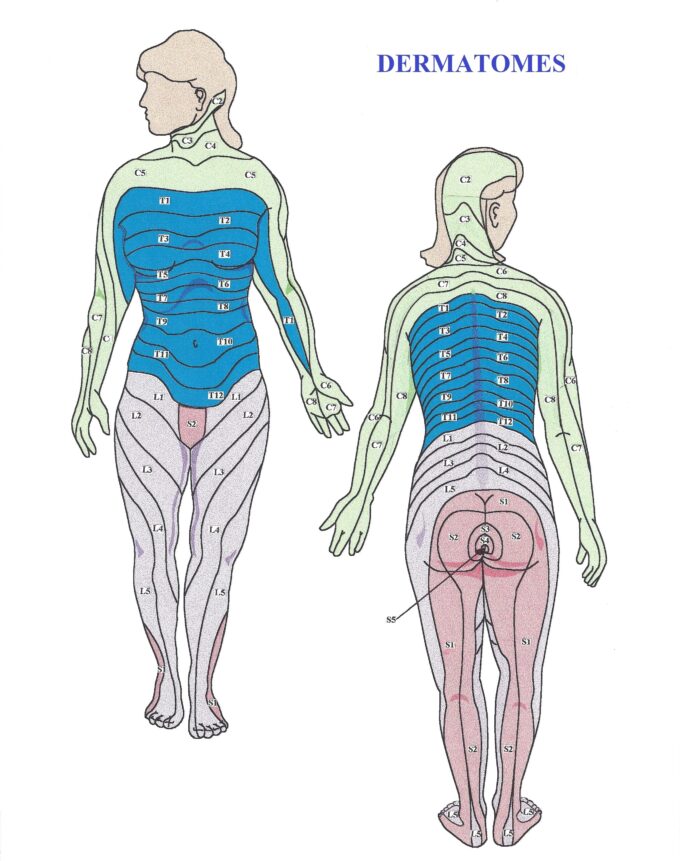

NCs form a wide network in the soft tissues, arranged in a dermatomal distribution. Fig. 2 presents a map of the dermatomes of the human body.

Each strip of skin corresponds to a specific segment of the spinal cord. Dermatomal maps are essential tools for initial clinical evaluation. They provide essential information: which spinal segment innervates the affected area?

For example, NCs in the C7 dermatomal zone project sensory input to the C7 spinal segment. However, only about 50% of the pain perception generated by the brain originates from the C7 dermatome. The remaining perception comes from neighboring dermatomes due to the overlapping phenomenon:

- 25% from C6

- 25% from C8

Because of this overlap, therapists must always include tissues from one dermatome above and one below the affected area in their treatment protocol.

FROM ACUTE TO CHRONIC PAIN: ROLE OF NOCICEPTORS

When soft tissues are traumatized or the nerve supplying them becomes irritated or compressed, NCs are immediately activated, producing a massive sensory inflow to the corresponding spinal segment(s). The CNS forms an acute-pain perception, and a person immediately reacts to that by withdrawal, guarding the area, limiting movement, seeking medical help, etc. These responses are compensatory attempts to reduce the nociceptive bombardment of the sensory cortex.

If therapy is not decisive during the acute stage (a very common scenario), the partial reduction of symptoms will trigger the transition of acute pain into chronic pain, which can last for months or even years.

FIRST vs. SECOND PAIN

- The initial acute pain carried by rapidly adapting NCs is called “first pain.”

- Without proper therapy, this evolves into the chronic or “second pain,” and it becomes the patient’s long-term burden (Basbaum et al., 2009).

The longer the “second pain” persists, the more hyperirritable and hyperactive NCs become. They begin reacting to stimuli that would never trigger NCs in healthy tissue (Walters, 2021). As a result, the patients developed layers of secondary pain patterns which present themself as the main problem during the evaluation. Longer chronic pain persists, and more layers of somatic dysfunction are formed, and they are hiding the initial trigger, which is still responsible for the entire clinical picture.

Additionally, within traumatized, chronically tensed tissues and/or irritated nerves, the initial inflammatory response is formed, and it contributes to chronic pain (Aley et al., 2000). The longer local inflammation persists, the greater the likelihood that it becomes self-reinforcing, significantly impairing the patient’s quality of life and contributing to months or years of suffering (Frias & Merighi, 2016).

WHAT TO DO?

We will discuss treatment strategies for controlling acute and chronic pain in the next article. To conclude Part II, we want to reinforce a key message:

Pain is not the problem—it is the consequence.

Pain results from a complex combination of various triggers. Our responsibility as therapists is to identify each initial trigger and its secondary reactions, and to eliminate them through a properly designed treatment protocol.

Always analyze the pain pattern reported by the patient, but never follow it blindly. In most cases (except for acute trauma), therapists encounter reflex and compensatory reactions that the brain employs to reduce abnormal sensory input from NCs. These reflex and compensatory reactions mislead therapy if not recognized, properly evaluated, and addressed.

As a final reminder:

“When nociceptors are overstimulated, they are capable of producing disabling sensations of pain and damage – even in healthy tissues (underlined by JMS)”

Armstrong S.A., Herr M.J., 2023

SOMI is seeking clinically oriented therapists who are willing to enter the professionally exciting field of MM to study its theory, soft-tissue evaluation, and the clinical application of MM protocols. Join SOMI for Live Webinar and Hands-on Seminars as a part of the Medical Massage Certification Program and inject clinical science into your practice!

Here is SOMI’s 2026 schedule: Medical Massage Courses & Certification | Science of Massage Institute » Medical Massage Continuing Education

REFERENCES

Aley, K. O., Messing, R. O., Mochly-Rosen, D., & Levine, J. D. (2000). Chronic hypersensitivity for inflammatory nociceptor sensitization mediated by the epsilon isozyme of protein kinase C. Journal of Neuroscience, 20(12), 4680–4685.

Armstrong S.A.; Herr, M.J., 2023. Physiology, Nociception. StatPearls

Baliki MN, Apkarian AV. Nociception, Pain, Negative Moods, and Behavior Selection. Neuron. 2015 Aug 05;87(3):474-91.

Basbaum, A. I., Bautista, D. M., Scherrer, G., & Julius, D. (2009). Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell, 139(2), 267–284.

Frias B, Merighi A. Capsaicin, Nociception and Pain. Molecules. 2016 Jun 18;21(6)

Marchettini, P., Simone, D. A., Caputi, G., & Ochoa, J. L. (1996). Pain from excitation of identified muscle nociceptors in humans. Brain Research, 740(1–2), 109–116.

Ochoa, J., & Torebjörk, E. (1989). Sensations evoked by intraneural microstimulation of C nociceptor fibres in human skin nerves. Journal of Physiology, 415, 583–599.

Sherrington, C. S. (1906). The integrative action of the nervous system. C. Scribner’s Sons.

Walters E.T. (2021) Nociceptors and Chronic Pain. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Neuroscience.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Here is a link to the author’s Bio: Medical Massage Courses & Certification | Science of Massage Institute » Editorial Board

Category: Medical Massage

Tags: 2025 Issue #3